On the podcast: From science fiction to science fact October 18, 2022

Lux Capital co-founder and managing partner Josh Wolfe joins the podcast to discuss why it’s always a good time to be investing in the future. From nuclear power to computers that can smell, Wolfe shares which technologies and sectors he is most bullish on and dives into his skepticism of the recent Inflation Reduction and CHIPS acts. Check out the episode to hear more about Lux’s strategies and which kind of companies—and investors—Wolfe expects to see survive the downturn. Plus, PitchBook analyst of fund strategies and sustainable investing Anikka Villegas shares insights from the latest PitchBook Sustainable Investment Survey and her recent analyst note ESG and Impact Investing in Private Market Real Estate.

In this episode of Sapphire Ventures‘ series “GameChangers,” Sapphire partner and Head of Revenue Excellence Karan Singh speaks with Procore Head of Corporate Strategy & Execution Ryan Butler about “unlocking the box” – how he has executed on go-to-market entry strategies, inclusive of new markets, product launches and segments or verticals.

Listen to all of Season 6, presented by Sapphire Ventures, and subscribe to get future episodes of “In Visible Capital” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts or wherever you listen. For inquiries, please contact us at podcast@pitchbook.com.

Transcript

Marina Temkin: Hi, Josh. Welcome to the “In Visible Capital” podcast. Very excited to have you. Lux is a very well-known venture firm, and many of our listeners are probably familiar with Lux. But for those who are not, please tell us about your firm and what differentiates you from what has become an increasingly crowded VC investment space.

Josh Wolfe: Lux today is 4 billion AUM. We’re half New York, half Menlo Park, and everybody is a generalist but we focus on really cutting-edge things. We always say that the gap between science fiction and science fact is always shrinking. About a third of what we do is in pretty cutting-edge things in energy, materials, physics, industrial and automation. Another third is in healthcare, and that’s everything from healthcare IT to biotech to … robotic surgery, all promised on breakthroughs in biology and biochemistry and where that intersects with computer science at times and increasingly AI and machine learning.

Then the final third is what we call core technology, which is more defined by what we don’t do, which means we tend to avoid things that are overcrowded—very competitive things where we find that there’s little technological differentiation, often driven more by marketing or by luck. Those are things like internet, social media, mobile, ad tech, video games, things that historically a lot of IT investors got into. For us, core tech is really these cutting-edge areas. It could be a brain machine interfaces, it could be autonomous systems, it could be defense, it could be space, but it’s things that, again, feel like they’re coming out of science fiction that might have inspired some of the engineers, scientists, entrepreneurs, inventors that we back.

About a quarter of what we do are actually de nova companies, so we will start them from scratch, either with a founder or principal investigator, scientist or start them from scratch—a partner might have a thesis. About a third of what we do being thesis-driven is looking at what everybody else is talking about and then often using that as a counter signal to figure out, OK, where’s the white space? What is nobody looking at? We love starting new companies and that sort of zero-to-one phenomenon.

Another third of what we do are people-driven investments. As the Lux portfolio grows, you get to tap into the cadre of entrepreneurs that are inside of a company and they might have vested, they might have contributed a lot of value, and then they’re thinking “Hey, I’ve learned a lot here and I want to have a partner of choice.” Ideally, we’re their first call as they go and leave one company and start another. We call it the Lux family, and it keeps growing.

Then the other style that we really like—and unfortunately, or fortunately, for the past decade there’s been very few of these situations—are special situations. Special situations are how do you invest in a late-stage business but at an early-stage price, which means something has happened that has impaired the cap table or the capitalization of the company, not necessarily the fundamentals or the balance sheet or the income statement or cash flow, but the investors. The investors are overextended, maybe they’re under-reserved as VCs, and there’s an opportunity for us to come in at a lower price than what the market might be bearing.

That is us in a nutshell. We really love the intersection of all these crazy disciplines and when we invest in a company we call it unam-Lux which means you get the entirety of the entire Lux team which includes all the investment partners, not just one that might be the core sponsor, our marketing function, our financial functions, our operations, our legal, but anything that we can do to help a company reduce risks.

Marina: Why is now a good time to invest in all these things that are so futuristic? The reason I’m asking the question is because over the last few years there was so much capital in the venture capital markets and you know that if you invest in something there will be more and more capital. You had all these crossover investors ready to invest a lot of capital to make these technological things happen—for instance, quantum computing—that are very capital intensive. What is going to happen now to products and technologies that are very capital intensive? Are they going to get funded, and what are your thoughts?

Josh: It’s always a good time to be investing in the future, because there’s always some entrepreneur that looks at something and identifies it and says, “That sucks. I want to make something better.” That’s been the history of the world, whether capital is abundant and cheap or capital is expensive and scarce. When capital is abundant, you have lots and lots of experiments that are getting tried whether they’re capital efficient or not. More money is going out the door. More entrepreneurs are starting companies.

Oftentimes, us being social primates and humans, we see somebody that you don’t necessarily respect as much and you say, “My gosh, if she or he just raised so much money, I can go out and do the same thing.” So you get copycat effects of people saying, “I can do a better job of that.” An investor might have missed company X so they investment in company Y.

All that just cascades and you get these bubble-like phenomenons when diversity among investors, growth, value and momentum all breakdown, people leave big corporate jobs and you just get everybody going into starting new companies and funding them. You go from this phenomenon of patient, analytical review of companies to FOMO, fear of missing out. The inverse, when capital is scarce, is that everybody is suddenly scared. People don’t want to be suckered, people don’t want to lose money. Maybe they lost money already and they’re suddenly gun-shy.

There’s this phenomenon that changes that people are suddenly reining in their wallets. If you have a portfolio, you may not be too quick to raise your next fund. You might have to increase the reserves of your current fund to support your existing companies. More companies might have flat rounds, they might have down rounds, they might have syndicates that are weak, they might have to make up for an investor that can’t invest or is choosing to triage a portfolio, and their best company might not be your best company. Our worst company might be somebody else’s best company. We might decide, “You know what? We have to find an off-ramp and a nice home for this company, but we’re going to help it find an acquisition, help the town find new jobs, but we’re not going to continue to fund it.” Somebody else might say, “Oh, this is the most important company in our portfolio.” You get this inter-fund conflicts that lead to a little bit of this interim chaos.

In terms of capital intensivity, the best companies will always be able to raise capital. Whether you are developing a pharmaceutical drug and you have to go through clinical trials, that takes upward of a billion dollars as a biotech company; if you are cutting-edge defense company like Anduril, where you are raising hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions, to have both a war chest balance sheet, but be able to develop technologies that are of critical importance to men and women on the front lines globally for US and our allies. I actually think that it is a great time if you are a super capital-intensive business, if you have an N-of-One company. Meaning, if you have a moat and you have some competitive advantage technologically, if you have some secret that you figured out about a market, then it’s OK to raise a lot of money.

In fact, in this current market, one of the strategies that we have, we call it the bubble, the anti-bubble, and consolidation. The bubble means, let’s raise enough money for certain new companies that can be relatively inoculated, immune in a bubble, not a speculative bubble but a protective bubble, from whatever might happen to macro, geopolitically, whatever might happen domestically with resurgence of Trump and political chaos or who knows, just protect them.

The anti-bubble is what I was describing before about the special situations which is, bubble is popped. [There are] great companies now at not-so-great prices for prior investors, but great for new investors. You can invest in these huge businesses at early-stage prices. But the consolidation piece is the last one, which almost requires capital intensivity. You want people that have hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billion-plus, of cash on their balance sheet. That allows them to do two things, it allows them to spend some of that cash on acquisitions and consolidate and rationalize the industry as other people who are cash poor are looking for exits and lifeboats.

It also allows, presumably if you’ve raised billions of dollars-plus, you have a reasonably fair stock currency to use. Combination of cash and stock will lead to consolidations, and we’re never turned off if a company says to us, “Hey, it’s going to cost us $200 million or it might cost us a billion dollars.” If we think that what they’re doing is going after a $50 billion price, then we actually think they’ll competitively advantaged because it’s just that much harder for other companies to raise money. It can be a net positive.

Marina: Yes, let’s focus on the anti-bubble and consolidation because I think the bubble part, that’s quite obvious. You fund companies that you really believe in, you allocate some room in your fund to continue to fund them even if capital is scarce. But the anti-bubble, the special situations, that’s somewhat different from what other venture capitalists are doing. Is this something that we didn’t see a lot of over the last decade? Also if you can describe a deal that … you would consider to be an anti-bubble or a special situations deal?

Josh: One special situation which I think is interesting goes back to a company called Luxtera. I want to say that the post-money when we first looked at this company, we were not invested, was around $225 million. Peter Hébert, Lux co-founder, myself, some others, were looking at it, but it was really Peter-led and he did a phenomenal job. He and NEA and some others came and recapitalized the business because they had funds like August Capital and Sevin Rosen and who were phenomenal funds in the prior decade, but the partners had retired. They called in the rich. They weren’t raising subsequent funds. So their ability to continue to invest in a company that still had a lot of risk was relatively low. Their LPs weren’t providing annex funds, which was a popular thing that you would raise another bit of capital to continue on for another year or two even though the lifetime of your fund had run out.

This was a company that was in a situation where it had a good balance sheet, it had a good income statement, it had good cash flow statements. So it as a fundamental business was doing fine, but its cap table was impaired, and it needed to raise a little bit of future capital. We came in and actually did a pretty aggressive recapitalization. That $225 million post-money valuation went down to $10 million pre. Management was refreshed. They were able to get significant equity. The CEO, Greg Young, did a phenomenal job of looking at the upside and sharing that with his key lieutenants. And that ended up selling to Cisco for $660 million just a few years later.

The rationalization of the evaluation to recapitalize it gave it the cash that it would need in the ensuing years, refreshed management who are feeling a bit fatigued, allowed them to recruit new people, and then ultimately have a great exit. They were making a component which is critical for last-mile fiber optics into data centers and computing. We know that there’s long haul fiber optic cables, but they came out with this interesting niche and it was still technologically early when they first developed it. It took longer than people thought. It cost more money than people thought. We were able to come in later on in that special situation.

There’s examples like that. There’s another one where a Freescale semiconductor, which was Motorola Semi, had a division that we looked at. We had an inside person, inside Motorola, who used to be a key VP of engineering and technology, and they said, “There’s this amazing jewel inside of Freescale Semi.” Freescale had just got taken private by The Carlyle Group, Blackstone, TPG, some of the big private equity giants. If you think about what they do as “The Flintstones” and what VCs do as “The Jetsons,” in cartoon parlance, we were he Jetsons.

We were willing to take this risk on this crazy little division that was developing non-volatile memory, which was a memory that basically didn’t need power and could be used in space and do all kinds of cool stuff. About $200 million had gone into that division and we were able to spin it out for, I think it was a $20 million pre. I think we got 50 people, 300 patents, $20 million of fully depreciated capital equipment, if memory serves right. Peter also, Lux co-founder, had led this one. Ultimately, we took it public some years later.

If you can really understand fundamentals of a business and what assets are there, what liabilities are there, the cash needs that it has, and basically think of it almost like a poker game—do you have a large enough chip stack to be able to see the next few cards flip over ante up?—then you stand the chance to collect the pot. We like those.

Marina: Do you see many of such opportunities now? Are you seeing many opportunities where companies are ready to recap? There’s still a bit of dry powder in the market and you would think that they would still be going to their original investors and asking for extensions and whatnot rather than doing this, which is a fairly dire situation?

Josh: It is and it isn’t. The short answer is no. I think we’re still early in the cycle and just like somebody that suffers a loss of a loved one or some bad news, we psychologically go through denial and anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, the clinical textbook examples of the five stages of grieving. I think some people are still in denial. I think some people have gone from denial and anger to bargaining. I don’t know that depression and acceptance have hit. Now, of course, the entrepreneur by default, and many investors by default, are bullish and look past the negative and believe that things are going to be great and things are going to be positive. It’s good to be a pragmatist, a realist, in tough situations.

It’s the kind of thing that can inspire leadership, loyalty, people not thinking that you’re delusional. Employees saying, “Oh man, they just don’t get it,” and sticking around because they believe like, “OK, look, we’re in a tough situation. We’re in a sector where we’ve got headwinds, people are cutting their budgets, our public comps are down significantly.” All that stuff can affect morale.

I think that you’re right that the first step is people will do extensions of rounds. The next step is people will give positive inducements to existing investors to participate. That might be some warrants or an equity kicker, some liquidation preference that increases, but it doesn’t negatively punish the non-participating investors. That would come next. Then you have pay-to-plays and the return of structure that not only rewards participating investors but punishes and disincentivizes non-participating investors from not participating. There’s consequences for that, so the carrot and the stick.

Then, I think, eventually you get full recapitalization. Now that doesn’t happen en masse across the board. There will be idiosyncratic company by company depending on what their situation is. That’s really the uniqueness of this is that in this crazy, chaotic, volatile market moment that will probably last for about two years, it isn’t like everything is suddenly going to be recapitalized, just a few companies will be.

It isn’t like everything is going to raise extensions around, some will, some won’t. It isn’t like some companies aren’t going to raise phenomenal, impressive up rounds or even go public. It’s really time to start discriminating between the haves and the have-nots, the good companies, and the bad ones, and ultimately you’ll see which investors are really wise and which ones were just following the herd and benefiting from a go-go momentum year, or set of years.

Marina: Along with a few veteran VCs, you’ve been very vocal about overvaluation in the tech market. The air has obviously come out of the tires this year. You’ve also said that you think that this was very similar to the dot-com bust. However, we still haven’t had many companies go out of business. There are layoffs, but most people who are losing jobs in the tech sector are able to find jobs in other tech companies. Do you think that this downturn is like the dot-com bust?

Josh: You described me as a venture veteran, which means that a veteran’s been through a tour before of this kind of stuff. In fact, that is my reference case, which you go back 20 years. I don’t know if it’s correct. I don’t know what the future will hold, but we look for analogies, we look for patterns. Sometimes like somebody seeing Jesus in toast or a face in the clouds, they’re not there. But the patterns that I see are, in fact, March of 2000 into Q3 of 2000, you had a surprise decline in the persistence of momentum in equity prices and suddenly something changed. Some of the poster children that were widely celebrated as being great investors suddenly became pariahs. They obviously weren’t that smart beforehand, they’re not that dumb now, it’s just a lot of attention was given to these folks.

From Q3 of 2000, you had range-bound markets that lasted for two years. What I mean by range-bound markets are markets that would give you these 1% to 2% daily moves, high volatility across the entire index. You would see some companies that would be up 5%, 10%, 20% and then down 5%, 10%, 20%. If you think about why prices are moving up and down like that, it’s the nature of the composition of the investor base that’s changing. You have a very significant passive indexation participation of investors that compose a lot of the holdings. I think you will see a return as we did back then from 2002 as this sort of all shook out—you can think of it as a bouncing ball with each ball bounce being a measure of the volatility of the markets; it’s bouncing high, a lot of volatility, bounced a little bit lower, until it basically was flat.

Then you had very low trading. That low trading was a measure of people’s despondency, despair, frustration recognition that the bubble wasn’t going to come back, that “buy the dip” wasn’t going to work in today’s parlance that the Fed put wasn’t there. This is, of course, even maybe worse or exacerbated as you have a global macro and a Fed environment of rising rates. You had a little bit of that in ’99 and 2000 with Y2K and Greenspan and rate rises that took the punch bowl away. You of course saw it in ’07, ’08, ’09 with the credit crisis, but it feels probably like that Q3 of 2000.

So, two years of range-bound markets that really went nowhere. Of course, there were some aberrations, some companies took off and some companies went bust, but by and large, the market just stayed flat. Then in 2002, two years later, you had the rise of the great celebrated investors who were these long-short hedge fund investors. They were people who were able to spot great compounding companies that would truly go on to become great lasting businesses still of today. They were able to spot those.

Then they were also able to spot the companies that might have had fan followings or retail investors that were basically fads or frauds or technologically obsolescent and would go out of business. Many of those did. I think you have that same phenomenon. The layoffs are real, and coming. I think that management always is loath to cut deeper than they ought to. You see a first wave of layoffs of 5% or 10%, maybe 15%, and then you see another round of layoffs but now it’s on a smaller denominator base of employees. When you really look at it, it’s closer to something like a 30% or 40% layoff rate. Snap obviously just laid off 20% of their workforce. Those people are not rushing out and getting jobs. And if they are, if you’re in ad sales, maybe you’re going to Facebook, but Facebook itself is starting to rationalize.

Some people have hiring freezes. I actually just think that you’re going to see a culling of the tech workforce and some of that will be a natural return to the number of participants in it. I think that a lot of the wealth effect that people had over the past few years is going to hit people hard as well. Where you were making fine money, you had a lottery ticket in some of the option value that you had, that now is basically worthless and entirely underwater. If you were speculating in the market, you’ve lost somewhere between 20% and 80% depending on how concentrated you were in some of the tech names. I actually think the carnage is going to be a little bit harsher, but it will take time for people to really feel it.

If that’s true, it’s natural, it sucks, it’s painful. Some people will lose money, some people will gain experience. By and large, the tech economy will continue to grow because the detritus, the failures, will be the combinatorial fodder for the next wave of entrepreneurs that puts pieces together and says, “Well, geez, we got rockets that are cheaper than ever and we’ve got internet and telecom that’s cheaper than ever. We’ve got AWS and now we’re doing this in biotech. We’ve got AI and machine learning models that are open source.” There will be endless creative recombination, but I do think that unfortunately a lot of people are going to lose a lot of wealth and have to restart from zero.

Marina: What about M&A? You’ve been saying that we will see a lot of M&A this year. So far, the numbers that we’re tracking here at PitchBook are not showing a pickup in M&A activity. When do you think that will start?

Josh: I think in biotech you’re starting to see it already. If you look at the publicly traded sector in biotech, you had 800 publicly traded companies, more or less. Half of them have less than two years of cash. A few hundred of them were trading at a negative enterprise value. I think already you’ve got biotech that M&A is picking up pretty significantly. I don’t have the numbers on hand, but I would reference you guys.

I think the number of deals, the size of them, and whether those are coming from larger biotechs buying smaller biotechs, pharma buying medium size biotechs, biotechs shedding assets and reducing their burn because maybe they were working on 10 different programs, now they’re working on two, what do they do with the other eight? They either divest them, they mothball them, they shut them down, or they sell them. I think sectors like that, that have deep carnage, the XBI, the biotech index, down to 60, did it hit a bottom? Maybe. Does it bounce along for a while? I don’t know.

I’ve been in these boardrooms and I know that some of these boardroom conversations are, “We had 10 programs, we don’t have the money. We can’t raise more, we gotta cut.” What happens when you cut is you try to sell stuff to recognize some value. I do think that there will pickup asset sales and M&A, particularly in biotech first. I think you’ll probably see it in software next. Again, anything where multiple contraction has happened significantly allows a buyer to re-look and say, “There’s no way we would’ve spent 40 times forward revenue, but now it’s trading at nine times forward revenue. OK, it’s a lot more interesting.”

Marina: Let’s turn to science and technology. Since science and technology are not always developed the way you expect, I’m wondering what potential technological innovation you were most excited about 10 years ago, and did they deliver on their promise?

Josh: This requires me to have an accurate recollection, and probably new technology for that of what I thought was going to be amazing 10 years ago. I’ll tell you, let me go back even further to fall on my sword, which is the area that I was most excited about when we were first starting Lux was advanced materials, and particularly nanotechnology, which itself was a broad catchall buzzword for innovations at the nanoscale that were happening in chemistry and material science. A lot of it was rebranded to capture the cachet and the hype and the buzz around it.

That was an area where I thought everything from carbon nanotubes and buckyballs and fullerenes to silicon nanowires, that was going to usher in a wave of innovation. In many ways it did. A lot of the things that we see now in cell phones from indium tin oxide that’s used for transparent touchscreens that we now take for granted, things in fabrics and clothing, things in OLEDs that are used in displays, a lot of that did materialize. It just took so much more time and money than even we had forecast at the time. I would say directionally right, but wrong in terms of timing.

Another area that I became very bullish on, probably a decade ago—and I think we nailed the theme and the way to play it, I’m still bullish about it now, although we’re not actively investing in it because it is something that is not shying us away because it’s capital intensive, but because of the regulatory risk—and that’s nuclear. Over the years rebranded it to elemental power, something I’m quite bullish on. If you truly are an environmentalist, you ought to care about the environment, and the best way to have very large, zero-carbon baseload power is nuclear energy.

We’ve got decades of safe reactors. We’ve have a handful of accidents often driven by human chains of decisions, as in the case of Chernobyl. Or an earthquake or tsunami, in the case of Fukushima, where we played an active role through a company that we founded called Kurion to help with the cleanup efforts, removing the radioactive cesium, strontium, technetium, uranium, plutonium from the waste streams that were coming when the government dumped hundreds of millions of gallons of seawater onto the reactors to prevent a meltdown.

Then there’s things like 1979 Three Mile Island, which was basically proof that engineer fail-safe systems work, and there wasn’t really a nuclear disaster, but it happened to coincide with “The China Syndrome,” which was a popular movie; it happened to coincide with the anti-nuclear war movement and the peacenik movement. All these things got inflated, nuclear lost a terrible branding initiative and a lot of support, unfortunately, from Greenpeace and other people that were like, “No nukes.” Now you have the former heads of Greenpeace that are calling for, “Oh my gosh, if you actually want to save the environment, you need nuclear.”

Nuclear is something that we are very bullish on. The particular thing that we decided to focus on then was waste, and what do you do with the waste and how do you clean it up? Then we frankly got lucky when Japan got unlucky with the Fukushima disaster and the technology and the team that we had assembled in this company, Kurion, had their life calling and rose to the occasion, and it was a great financial and moral and qualitative success. I was very happy about that.

Today, probably the technology that I’m most excited about is something that I’ve been on a decade-long quest for. Again, you have to discount a little bit the bias that I have that I’ve been looking for so long, and kissed a lot of frogs and found a lot of entrepreneurs that weren’t backable or a lot of science that wasn’t differentiated, but we finally did find something now. We’ve funded it along with some great investors and it’ll come out of stealth in the next month. It is for digital olfaction. The devices that we carry can capture sight and sound and you can do high-speed, time-lapse, 4K, high-def video; you can capture perfect stereo audio. You can’t capture smell, until now.

The ability to give computers a sense of smell, which allows you to do everything from have a Shazam for smell, you walk into a room or you have a meal, or you’re capturing a moment, the smell of a loved one’s hair, the nostalgia of an old family home, whatever it might be, to be able to capture and record that. The ability to detect human health from breath, that’s COVID-19, cancer, epilepsy, Parkinson’s, all kinds of stuff where we know that dogs can smell these things. Then industrial and defense applications, whether it’s detecting electrical fires or other off gases that you might want, huge application for that.

That’s something that never existed before, and the “why now” is really less about the sensors, which continue to evolve, but more about the graph and neural nets and the AI that has trained on so many different smells and can now predict, when it encounters a molecule, what it is.

Marina: That is very exciting because I know you’ve been on the search for this company for some time, so it sounds like it’s coming out of stealth very soon. We’re definitely looking forward to covering that. What about gene sequencing in CRISPR? Some scientists say that it’s under-delivered on its promise so far. What do you think?

Josh: Under-delivered on its promise in that you really only have one or two drugs that are gene therapies that have really hit the market. Spark Therapeutics was one, but I would say that it’s more criticism that we get over-excited about things in the short-term and then historically tend to underestimate them in the long-term. We have another company that’s going to be coming out of stealth that takes one of the co-discoverers of CRISPR and his work and pairs it with an incredible suite of delivery technologies, which is really the biggest problem that has held back CRISPR, which is how do you do targeted-delivery of gene therapy to a specific organ or even a specific cell?

That has been very hard, and I think that this team now has figured that out. The way that they figured it out itself is a mind-blowing story, but we’ll save that for another time. I’m actually quite optimistic about it. The ability for us, when you think about even the pandemic to go from having a unknown illness to sequencing the nature of that virus, to discovering and synthetically creating multiple forms of mass RNA vaccines really in the course of—even though it took many months to a year for the full distribution of it—days and weeks, is just absolutely stunning validation of human ingenuity and achievement in the compounding nature of all these things that have been two decades-plus since the human genome projects existence.

I am very bullish about gene therapy, genetic editing, some of the computational approaches to be able to search through the genome, identify proteins of interest, look at protein-protein interactions, look at the molecular glues that can help to bind them, look at the ion channels that, in some cases, because of mutations, create everything from conditions like cystic fibrosis to potentially Parkinson’s. Those are all areas where we’re actively investing. I see true geniuses looking at the structure of biology, the underlying genetics, the code that is in our genes, and computational approaches to discover drugs. I’m super bullish.

Marina: Do you feel that meaningful technical innovation is slowing down? Last century, we’ve had some huge breakthroughs and mass-produced cars, commercial air travel, refrigeration, those inventions made a meaningful, huge improvement in people’s lives. Now that’s slowing down. We’re not having such huge breakthroughs that really improve the quality of life. Do you agree with that? Disagree? What are your thoughts?

Josh: No, I disagree. You have the Robert Gordon view that some of these innovations were the most– The short answer is it’s because those past things are observable. In a sense, you can almost exaggeratedly say it’s like looking at the music of anybody of a given ages, period from 16 to 24 of their life where they would say, “Oh, current music just sucks compared to the old music.” Of course, it’s a very visceral feel. Of course, toilets and air conditioning were absolute game changers, but look at what happened during the pandemic.

Our ability to take for granted the fiber optic cables that went around the world globally that really cost anybody virtually nothing. The ability to have compression algorithms that allowed us to do video conferencing. In 20 years, we will look back and say there hasn’t been anything like the fiber optic cables and the compression algorithms that allowed the entire world to compress ourselves from three dimensions into two dimensions, and avoid talking.

To me, it’s astounding how the near-term innovations are overlooked. We were just talking about the vaccines. In history, the fastest that humans ever came up with a vaccine was Ebola, and I think that was five and a half years. The ability to vaccinate a significant portion of the world is just astounding, and the speed with which we did it. Not only from the discovery of, again, the sequences, but the manufacturing and the conditions they’re in. I just reject the premise that the rate of innovation is somehow slowing.

What is changing, and it is observable, and I think this is a good thing, is that of course, 200 years ago—and this is almost evidence from my point—a single person might have been able to know much of what was really important to know on the cutting-edge. As people became more and more specialized over time, as the boundary of what is not known, or what is known, keeps expanding, it also reveals. And I always like to say this about Lux. Lux itself is Latin for light. You shine a spotlight, anytime you look at a spotlight in the dark, the circumference of that light is all the unknown. As that spotlight grows, that circumference grows, so too does your awareness of what’s not known.

That has led to specialization. Instead of somebody being in a biology department, now you have statistical biology, you have biochemistry, you have computational bio, you have biomechanics. The increased specialization means that you have all these interdisciplinary groups, and that is often where we find the biggest innovations, where the computer science department was never talking to the biology department. Now you have entire buildings that are newly endowed, that are the interface between computer science and biology.

Same thing with material science and computer science. You have aerospace and the entire space economy launching satellites that can not only stream down our SiriusXM Satellite Radio but TV and content and take pictures and reveal truths on the Earth, whether they’re migratory crises or geopolitical preparations, as we saw in the case of Russia as reported by some of Lux’s companies.

I just truly believe that innovation continues to compound, that it’s easy for us to oversee and take for granted all the technologies that we see around us. We tend not to notice them until they break. I just think that the endless frontier of combinatorial possibilities is going to increase.

I’ll give you another example, which is all the things that start out trivial, like a depth-sensing camera that’s used by an Xbox or a PS4 for “Just Dance” or “Dance Dance Revolution,” which my kids play, can detect their body movements and whether or not they’re in choreography sync with a hit song. Some genius came along and said, “What if I took that capability of those 3D depth-sensing cameras and put them into a rapidly turning camera that could do one of two things?” It could statically capture an entire room or physical space and scan it. People talk about the metaverse, but the ability to take physical objects or lift spaces and rapidly scan them and capture them digitally is really important. If you spin something like that in a much faster frequency, you get lidar, and now you can get, effectively range-finding radar for autonomous vehicles.

All of these things compound and they’re beforehand never predictable. Same thing in gaming. The GPUs that were allowing for graphics innovations as we ever increased in Zelda from small pixel pitfall that you played in Nintendo to cutting-edge PS4 today, those GPUs became the new soul of the machine for all of the AI and machine learning researchers who are doing all the things now, like Midjourney and Stable Diffusion and DALL-E that are able to take gigabytes of known artists and then synthesize that body of work into algorithms that with a simple text prompt, can generate anything that your mind can literally imagine. That is just mind-blowing. Now, you take that and you start to apply it to scientific research literature, video. I just really feel like the possibilities are endless and inspiring.

Marina: You mentioned Russia and the war in Ukraine. You were one of the few VCs that have been investing in defense companies. Are you seeing more interest in that from other firms? What are your thoughts?

Josh: We are, us and a handful of other firms, have been relatively early investors in companies like Anduril, Saildrone, Clarify, Varda, Hadrian, that are either manufacturing what we would consider the arsenal of democracy, the return of the “freedoms forge.” The tools, technologies, hardware, software that either are manufacturing key components of aerospace and defense, manufacturing satellites, manufacturing drones or creating entirely new paradigms for a defense that people historically did not want to work on.

When I say historically, I really mean the past generation. Really since the early 2000s, you had a movement of people that felt it was taboo. They didn’t want to work for the Pentagon, they didn’t want to work on cutting-edge technology. We’ve warned for a while, the world is a dangerous place. Why would you not, especially if you spend time with some of the brilliant women and men on the front lines in all branches of our military, why would you not want to equip them with the best technology?

We actually felt it was a moral good to make sure that the United States, which I truly believe defends the best of our liberal democratic values—although, again, the short term, it feels at times like that’s being a fabric that’s ripped apart by various forces. We got long and loud about many of these companies that in every stratosphere of the Earth from space, air, land, sea, software, cyber, are all, in our view, fighting the good fight. We believe it’s a moral good that you can reduce human suffering by inventing and investing in technologies that can deter war.

Increasingly, you’re seeing people, not only investors, but more importantly investors are looking at the signal of where smart people want to go. Smart people increasingly don’t want to just work at Facebook reinventing ads or working on Google for search. They want to work on really important mission-critical stuff. When you see a revanchist Russia or an increasingly bellicose China, particularly the CCP, I think people see that there’s a long-term mission calling here and it’s inspiring a lot of folks.

Marina: What opportunities are there for startups from the two recent pieces of the legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act?

Josh: I am very skeptical about both. I think the CHIPS Act is going to effectively help to subsidize some old guard, Silicon Valley companies like Intel that are themselves through business model shifts. I prophesied, predicted, or forecast some time ago that Intel would effectively become like TSMC. Now that’s a good thing for domestic security for us to be able to have our own foundries that can produce chips that are mission critical. But Intel is not necessarily at the forefront or the vanguard of making the most important chips.

Historically for PCs and servers, they’ve lost the mobile race to ARM, they’ve lost their GPU race to Nvidia. I see a resurgence of new cutting-edge chip companies that are basically going to change the economics of how you manufacture this stuff. Not requiring class 100 or class 1000 cleanrooms, but coming up with new design architectures that flip a whole generation of semiconductor manufacturing on its head, flip chips, chiplets, all kinds of interesting new techniques.

I think that, if anything, tax incentives and money should be going to the new companies. I understand the geopolitical will and the support to “shore up” the demand and the tense of CapEx that is in accordance with Rock’s Law, which is parallel to Moore’s Law. Moore’s Law, more chips for every dollar every year and a half, Rock’s law, insanely expensive every two years, and more so to build another fab that can get us to the next, sub-20 nanometer node. I think most of it will be wasted money, unfortunately, going to some of the big old school semiconductor companies.

On the Inflation Reduction Act, I have a view here, we have a view at Lux which we’ve called biflation. I don’t see government intervention here helping. I see it actually exacerbating. It historically always has. The Fed itself, I think, waited too long to raise rates, and I think they’re raising them too far now. I’m not saying that because I want them to lower them so that equities can be speculative high. I think they’ve taken some, if not most, of the speculative excess out of the equity markets, which is good.

Rising rates hurt the poorest the most. I’ve called this the treadmill class economy, by which I mean there’s wealthy people who have Pelotons in their homes and can afford treadmill classes and go to Barry’s Bootcamp and all that. Then there’s poor people who are quite figuratively on a treadmill. The job numbers that you see that are going up are people that have to go back to work because their Robinhood accounts or their crypto accounts that they were speculating on the side are busted and they need to make ends meet at a time when you have consumer stables that they need rising in price, affordability of their stuff declining in price, and interest rates rising. Most people don’t have $400 or $600 in savings to hit a medical emergency. They’re in a really tough bind, and you’re raising rates and the cost of capital and the availability of it and the liquidity that people need at the worst time. Interest rates north of 20% for a credit card, I think that’s a tragedy.

Then you have the other end of the spectrum—that’s all inflationary on prices and must-have things and the affordability is going down. At the other end of the spectrum, you have declining prices for all the consumer discretionary stuff, which again, are like the Pelotons and the Nikes and the Under Armours and all the stuff that people pulled forward both in fashion and retail and turning their homes, during COVID-19, into three-star hotels with spas and everything. You don’t need any of that stuff anymore. You pulled 3, 4 years of demand forward. I see this biflation between the upper-middle class and the wealthy who actually see declining prices and the poor who are actually seeing rising prices.

The Fed is basically trying to land this plane, so to speak, but I think they’re hurting the worst the worst. I think it’s a shame. I think this Inflation Reduction Act is just going to create all kinds of unintended consequences like the government always has.

Marina: Speaking of regulation, Congress has shown themselves to be behind the curve in the past, most famously during Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony in 2018. Is there a lack of oversight beneficial for technology as a whole, or would they be better off if they were on top of regulating these industries?

Josh: I think when it comes to regulation, the government, and this includes both the SEC and Congress, are always involved in the autopsy, not the diagnosis. Meaning, after people have lost money, after people have suffered, then they come in as the police to slap somebody’s wrist. By the time that has happened, it’s too late on the public market side or the investor side for the SEC and on the Congressional side, interventions.

When you look at the history of monopolies, every time the Department of Justice knocks on a door and basically says, “We’re going to go after you”—whether that was Microsoft in 2000, Google Search in the 2010 time period, Facebook more recently—there’s always a competitor that through the free market and entrepreneurial ambition and investor greed, is funding the very thing that will basically undermine the monopoly itself.

Microsoft in late ’90s, early 2000, when Joel Klein was going after Microsoft for bundling and unfair practices and investigate browser and Microsoft Office and all that, they didn’t anticipate Google. Then Google is rising and Google didn’t really anticipate Facebook. Now Facebook is rising and people are lambasting it but Facebook has already done its own damage. Most of its products lack the one essential feature, which is trust. Very few people trust Facebook. A lot of people trust Apple. I think that there will be a set of emerging competitors and certainly a dominant one that comes, that is a greater regulator and a natural one to Facebook.

Which is some, as yet, unknown competition, but they will get disrupted not by the DOJ or by Congress regulation, but by the ambition of some other entrepreneur that’s like, “Facebook sucks and we’re going to come up with a better version.” Same thing like, “Zuck’s metaverse sucks and we’re going to come up with a better version.” Rather than look at their current dominance and size of their scale, I’d be looking at who’s the motivated entrepreneur that’s like, “I’m going to take those guys down.”

That’s what I would be betting on more so than a bunch of theatrical lawyers. That stuff mattered far more before the 1980s, before venture capital industry, before you had industrialized greed that could back entrepreneurs’ ambition. Now that we have that, you need to let the free market do its thing and let creative destruction happen and I think we’ll be better off. I’m long creative destruction and entrepreneurial ambition taking down Zuckerberg and Facebook faster than the DOJ will.

Marina: Great. Before I let you go, I’m wondering if you can suggest a new emerging tech area for PitchBook to cover. We have a team, it’s a handful of analysts who cover emerging tech areas broadly. There is an analyst focused on healthcare, one on AI and machine learning , one on climate tech, one on mobility, and one who covers fintech and crypto. I’m wondering what do you think is the next area of innovation that we should focus on broadly?

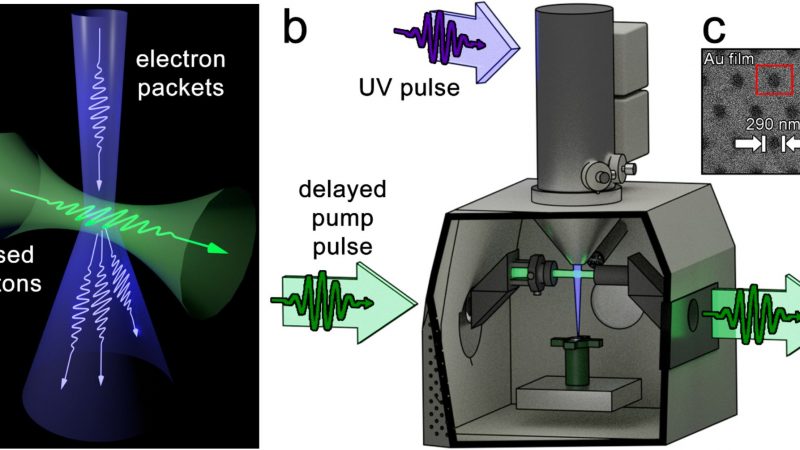

Josh: I think the biotech and tech bio intersections are really important. Beyond healthcare, the intersection of computer science, AI, machine learning and biotech is really exciting for us. We have a lot of investments and growing. Another area that I think is really important and interesting is what I call the tech of science. Just like you have the hard power piece of defense, which is directly focused on hardware and software for military use, there’s a soft power piece on the global stage. Soft power comes when you win Nobel prizes and you win Nobel prizes by having cutting-edge instruments.

There are a lot of smart engineers at multidisciplinary intersection of optics and lasers and AI and software and machine learning and imaging that are doing just incredible sci-fi-like work to provide tools to scientists to make new discoveries. That entire domain of lab automation, cutting-edge instruments, scientific tools, the software that is allowing scientists to both run their labs efficiently and make predictions from AI and generate new hypotheses. I see tremendous innovation and a revolution of affairs there.

Marina: Thank you, Josh. We really enjoyed speaking with you today.

Josh: Great pleasure. Thank you.

In this episode

Josh Wolfe

Co-founder and Managing Partner, Lux Capital

Josh co-founded Lux Capital to support scientists and entrepreneurs who pursue counter-conventional solutions to the most vexing puzzles of our time in order to lead us into a brighter future. The more ambitious the project, the better—like, say, creating matter from light.

Josh is a director at Shapeways, Strateos, Lux Research, Kallyope, CTRL-labs, Variant and Varda, and helped lead the firm’s investments in Anduril, Planet, Echodyne, Clarifai, Authorea, Resilience and Hadrian. He is a founding investor and board member with Bill Gates in Kymeta, making cutting-edge antennas for high-speed global satellite and space communications. Josh is a Westinghouse semi-finalist and published scientist. He previously worked in investment banking at Salomon Smith Barney and in capital markets at Merrill Lynch. In 2008 Josh co-founded and funded Kurion, a contrarian bet in the unlikely business of using advanced robotics and state-of-the-art engineering and chemistry to clean up nuclear waste. It was an unmet, inevitable need with no solution in sight. The company was among the first responders to the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. In February 2016, Veolia acquired Kurion for nearly $400 million—34 times Lux’s total investment.

Josh is a columnist with Forbes and editor for the Forbes/Wolfe Emerging Tech Report. He has been invited to The White House and Capitol Hill to advise on nanotechnology and emerging technologies, and is a lecturer at MIT, Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Columbia and NYU. He is a term member at The Council on Foreign Relations and chairman of Coney Island Prep charter school, where he grew up in Brooklyn. He graduated from Cornell University with a Bachelor of Science in economics and finance.

Sponsored Content

Karan Singh: Welcome to our segment of the program that we’re calling Game Changers, where we’ll explore how the best revenue leaders have transformed their company’s growth trajectory. I’m your host, Karan Singh Partner and leader of the Revenue Excellence function at Sapphire Ventures.

Joining me today is Ryan Butler, Head of Corporate Strategy and Execution at Procore. Ryan, great to have you on.

Ryan Butler: Thanks, Karan. Nice to be here.

Karan: Amazing. So Ryan, let’s dive right into it. I always like to start by learning a little bit about our guests, and I know a little bit about Procore. I was at Procore for some time too. And it’s funny, every organization has its superpowers. I would make the argument, and I’ll contend this to anyone who asked me that our corporate strategy organization is our superpower at Procore. It has aligned the organization incredibly. So that has a lot to do with you, Ryan. With that, I want to hear a little bit about your background, not necessarily just your baseball card, where you’ve been, but I like to hear about your big aha moment.

Ryan: I think my big aha moment, it came a couple of years ago as I was looking at alignment across our organization, and that’s supposed to be my job, is aligning different functions and all pushing everybody in the same direction. And I noticed that we didn’t really have alignment in terms of where we were going from our sales strategy and how that flowed back into our product strategy and the rest of the organization. So I think my big aha was how do we start to bring those two organizations or those two strategies together into one and actually be going after the same goal.

Karan: Got it. So that alignment, being at the undercurrent of everything we do, I like that and I do recall that being a game changer. So at the risk of guessing, I’m going to ask you what is that big game changer you’ve had and done and led as an organization?

Ryan: We ran a project that we called Unlock the Box back at the time where basically we started with a pretty basic market segmentation and total addressable market or TAM exercise and actually tried to figure out how to use that to size the different opportunities that Procore could go after and really start to focus everybody on what mattered most first, next and last, and what was needed to drive success over what timeframe, and really got very tight on what were we going after now and how is that going to contribute to Procore’s success in the next quarter and year. And then what do we need to be doing now to contribute to the success that we wanted to have in the out years? And that project really became the basis of what we think about as our strategy and our planning process today.

Karan: Let me counter that a little bit for you because I do agree, I think having that alignment is really important, but whenever I sit next to say, a revenue leader, a sales leader, more often than not, whether it’s right or wrong, they’re going to sit there and say, “Hey, I know exactly where to go, what to do, how to go do it, and I just need support to be able to go execute.” Most of us fancy ourselves arm share strategists anyways. Let’s talk about Procore in particular. What made the organization look around and say, “Hey, we actually need this versus what we were doing already.”

Ryan: The way that you go about doing this and not coming from an ivory tower mentality of, “Hey, I’m not the one closing the deal, or I’m not the one building the product, but here’s what I think.” And it really has to be a collaborative project together to all agree on those things. And I think everybody has a great sense of the individual parts of what they can see as being important, and then it’s really like how do we agree on those things and put them together?

But I think the biggest, the aha moment was basically, Procore is a very sales led company at this time, and so we were growing very rapidly and the sales strategy that we had was working, but it was starting to show strains on the rest of the organization, meaning the sales leaders were out there and they were closing an amazing number of deals in different markets in different countries and really growing the basis of the business. But we started to see many different types of customer requests come in from the deals that we were closing or had closed and many different strains on our GNA organizations to be able to support those different markets. And we started to run into this problem of what was most important.

Karan: I know our CRO at Procore used to say this, which I liked, was most companies die of indigestion, not starvation. And I think there was a little bit of indigestion happening. So you’re right, revenue absolves all’s things, but if you look under the hood, there’s more there and if you can get in front of it before you hit those macro headwinds or growth pain points, things like that, it’s incredibly meaningful. It helps you keep that trajectory going. So with that, obviously we’re not just going to talk about the theory of alignment, let’s talk about how we actually do it. And again, you are one of the best when it comes to executing and being really sequential and thoughtful about what we do, like you said, first, second, last. So give me a sense, Ryan, walk me through that journey.

Ryan: The first thing that we actually had to do was agree on our segmentation and the opportunity size of that. And it sounds incredibly basic I’m sure, but at Procore and at every company that I’ve ever worked at segmentation can get pretty complex when you get down into details. And so for us it’s this Rubik’s cube of geographic location, type of construction company, so general contractor owner, specialty contractor, trade contractor, size of the company, and then product as the type of product they want or where they play in the construction life cycle is another way that we had looked at segmentation. And so the first problem statement was essentially everyone talked about the segments differently and didn’t actually understand how they came together and what were the different sizes of those different opportunities. And so the very first step was just coming up with a segmentation framework that was common across the company that we could all agree and speak the same language to each other. And then we actually had to run an opportunity sizing project on the back of that to go out and say, “Okay, what was the addressable market opportunity?”

Karan: Makes sense. And I think whenever I advise companies, I see a lot of them having that long range model, that TAM, SAM, SOM assessment. Inevitably though getting your sellers to look at it or your revenue arc to look at it and say, “Yeah, I believe that.” That tends to be hard, especially when data is such a challenge when it comes to getting this thing dialed in. So I’m curious, as you went through and set the stage on what that segmented TAM is, did you involve your sellers in that process?

Ryan: I’m a big believer that the field has to be involved in all of the strategy that you do. So your customer has to be involved in any strategy is only as good as how well you understand the customer. And the people who typically understand the customer the best is the field and so you have to have them as part of any project like this that you’re doing and they have to be a feedback loop. Now you have to do it in a thoughtful way because the field has more important things to do than some of these theoretical projects that you’re trying to drive, or at least at the time, theoretical and so we had to be thoughtful about it. But the way that we did it is we actually used our sales engineers as our counterparts in some of this to partner with us as our feedback loop into this and then our testing ground for what made sense to them and what didn’t.

Karan: And yeah, I love that. You have to be mindful about how much you asked too, but if you don’t bring them along, it can be really painful later on. So you went through that exercise, you defined a segmented TAM, you went through and socialized it along the way, got progressively better over time with it. What was next?

Ryan: Yeah, now we had to understand what was different about each segment. And so once you can understand the opportunity size, the next question is basically what would it take to go win that opportunity? And so our thought process in doing that was first to set a baseline. We had a customer type one of those segments that we had been focused on for a while and had had great success at a Procore. And so our first step was, let’s go back and retrospectively say we weren’t in this segment and look at what does that segment need? What would it take to win that segment? Even though we had many of those things at that time, but what were all of the key go to market needs that we had that contributed to our success? What were the core product needs that were more and less valuable to that market? Anything that we needed to support product and go to market from an operational standpoint. So what was that basic needs checklist for a market that we knew very well?

And that then became our baseline. Once we had a baseline of saying like, “Hey, this is a framework for understanding what it took to win one segment, one market that we knew very well.” We then went and ran a research project again involving our sales team and our product team together to go systematically look at the different segments within our matrix and say, “How is this similar or different to the baseline that we understand?” So we’re going to a very different type of construction audience. We’re going to a very different size of company. There are some common needs that they have. If you just take a product perspective, they need very similar things that a construction process is very similar, but then there are X number of things that are very important to them or differently important to them than the baseline and how do we start to quantify those differences?

Karan: You know me, I’m an operator at heart, so I don’t think any strategy can actually turn into a plan into execution until you start talking about KPIs, you start talking about the targets against those KPIs. So effectively how are you measuring success?

Ryan: The first real indicator is alignment and how many people that you’re meeting with actually are speaking the same language that you’re speaking when they’re talking about segmentation and at least have the same general knowledge and the same general framework that we’re all operating off. The next thing that we did, the next KPI that we focused on was product adoption of this. So the more we felt that we could get product understanding the common needs and understanding the prioritization of the common needs and getting that into the product roadmap, we felt like that we could then more appropriately start to bring the rest of the organization around where the product was going. Because for us, we want to be led by the strategy that we have that’s one, two, three years out. And the more product is ingrained in that the more they’re going in that direction, the more everyone starts to follow.

The next thing that we did was actually work with you directly, Karan, to start to, you ran our revenue planning function among many other functions. And so we started to work with you to think about how can we build in our idea of what we’re prioritizing and which markets that we’re going after into the revenue plan. Because if we can get target set on the back of what everybody else says is important, then naturally the rest of the sales organization is going to go after where their targets are at. And so our KPIs then were how well are we baking in what we think is the opportunity size of the markets we’re prioritizing into the revenue plan? And then you just have to essentially then you just track the KPIs of the product organization of the revenue organization with the KPIs of this project. And as you start to see some of the product development KPIs fall off, and maybe that’s a reason that you need to go and change your strategy.

Karan: Speaking of a wide audience that is probably trying to do the same things that you’ve already accomplished here at Procore, and I know you’ve been on a three, four year long journey here with respect to, but what did you learn? What would you do differently? If you got to start over from the beginning, how would you sequence this?

Ryan: The thing that I definitely would do differently is all of this sounds nice as we’re talking in a podcast, but it was a pretty bumpy year and a half until I got to the point where I was getting product to adopt it. And then I was probably another six months after that, Karan, before I actually start to be able to work with you to start to get the buy in to get it into the revenue plan. And so I lost a year basically because I didn’t start and get buy-in at the top of the organization down. But we should have started framing the problem statement up to the executive layer, making sure that we all had buy-in, that this was a key problem statement and then started to bring them along in the journey more effectively.

Karan: You know what’s interesting about that? In the last couple of podcast episodes I’ve done as well, one was around growth marketing and ICP, the other one was around value selling. Completely different topics than this one even. They all had the same commonality on what would you do differently? What would you do better earlier? Which was, “Hey, I wish I’d pitched earlier. I wish I’d had gotten a common, some alignment amongst the organization that this is an important initiative to go after.” So it’s maybe a learning for all of us as we go down any business transformation key initiative. I don’t think we spend enough time early days talking about the why. Before we jump into the how.

I’d love to finish these conversations with a lightning round. Don’t think too hard, just your gut reaction for each.

Great leaders pick great companies, Ryan. How did you pressure test that Procore was a company you wanted to go to?

Ryan: The culture and the people. If I don’t see people I think I can work with every day and incredibly smart people, then I feel like I’m going to fizzle out in this company. And Procore had that in spades.

Karan: How did you make the transition to leadership and what would you share with others on that journey?

Ryan: I think the transition for me was how do you go from a doer to a teacher? I’m somebody who likes to get my hands in my new details and likes to get my hands in actually thinking through and writing out or modeling things myself or actually being the one who is the thought leader, developing the thought leadership and that just doesn’t scale. And so I’ve had to make a transition, some would say rocky at times too. How do you teach other people to do that or how do you learn from the way they do it and integrate that into what you do? And I think that that transition to teacher has been the biggest thing that I would tell people to focus on.

Karan: I love that. Biggest misconception about your discipline?

Ryan: I get a lot of like, “Oh, you’re just that guy in the ivory tower that doesn’t actually understand how any of this works. You’re just a suit, for lack of a better word, that doesn’t really understand how to get things done.” And I think that could be very true at a lot of different corporate strategy functions. And I just really work with myself and my team to pride ourselves on understanding and getting into it with the business and really helping to being someone who helps and assists the business rather than someone who antagonizes or tells the business what to do. And so I think the way that we combat that misconception is just by rolling up our sleeves and trying to actually be operators with everybody else.

Karan: Last one. And it’s a fun one. If you weren’t in corporate strategy, what would you be doing?

Ryan: If money was no object the thing that I would really want to do is be a stay at home dad. I get a lot of joy outside of work from playing with and learning from my seven year old daughter. And so I think if I could do something else and I didn’t have to work, that’s what I would be doing.

Karan: I love it. I think you know me well enough to know that I would be the same with my three little ladies too.

Ryan: Yeah.

Karan: So we’re one and the same, my friend. Right on, Ryan. Really appreciated my friend and great conversation. Glad we were able to have you on the show.

Ryan: Thanks for having me.

Karan: I’m Karan Singh, and this has been the Game Changers podcast by Sapphire Ventures. To stay up to date with company news and announcements, be sure to follow Sapphire Ventures on LinkedIn and @SapphireVC on Twitter.

To get all the latest trends, best practices and resources from revenue operations experts for startup growth, subscribe to our web ops newsletter, info.sapphireventures.com/subscribe.

Nothing presented herein is intended to constitute investment advice, and under no circumstances should any information provided herein be used or considered as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy an interest in any investment fund managed by Sapphire Ventures, LLC (“Sapphire”). Information provided reflects Sapphires’ views as of a particular time. Such views are subject to change at any point and Sapphire shall not be obligated to provide notice of any change. For more information, please visit Sapphires’ website at www.sapphireventures.com.