Why Neal Stephenson is trying to make the open metaverse into a reality

Did you miss a session from GamesBeat Summit Next 2022? All sessions are now available for viewing in our on-demand library. Click here to start watching.

The metaverse has been trending for a couple of years as humanity’s answer to the pandemic and remote work. Neal Stephenson, the author of the science fiction novel Snow Crash and cofounder of blockchain tech firm Lamina1, is the high priest of this metaverse religion, as he coined the term “metaverse.”

And after 30 years of waiting for science fiction to become reality, he doesn’t want the metaverse to turn out to be a dystopia. Concerned that big tech companies like Meta could turn the metaverse into a bunch of walled gardens, Stephenson cofounder Lamina1 with Peter Vessenes to spearhead the open metaverse.

I spoke with Stephenson in a fireside chat at our GamesBeat Summit Next 2022 event last week. We talked for a while and then Stephenson answered questions from the audience.

Stephenson said that the metaverse should have a lot of people running around in it and a unified geography. He doesn’t think you should be able to randomly jump from place to place.

He also talked about how to do research to get people to believe in your fiction, and that’s why he has so much technical material in his science fiction books. Stephenson related the surreal experience of seeing Snow Crash become so popular in its 30th year.

From time to time, startups have tried to take the things in his books and make them real. But Stephenson said he has been reluctant to endorse any particular implementation of his ideas. With Lamina1, he can work on underlying infrastructure that will make a wide variety of metaverse interpretations possible.

In his view of openness, he believes economic transactions should be transparent. And he thinks people who contribute things to a solution should have their contributions tracked, and compensated if it’s worth something.

Stephenson talked about his view of blockchain technology, and why it can be used to create a decentralized metaverse. He also believes that games will lead the way to the metaverse, as we need to have something fun to do when the metaverse arrives. Game developers are also the ones who are competent enough with the 3D game engines that must be used to create the 3D animations of the metaverse.

Perhaps the most interesting topic was what he would do if he had to write Snow Crash over again, set in the future 20 years from now. We also talked about climate change and the crossover between solving the problems of the metaverse and the environment at the same time. And he also answered a question about his favorite game.

Here’s an edited transcript of our talk and the audience q&a.

GamesBeat: Thank you for staying for this special treat here, and thanks to Neal for doing this.

Neal Stephenson: It’s good to be here.

GamesBeat: Does it sometimes feel like you’re the high priest of the metaverse religion?

Stephenson: Really, I’m the weird monk in the cave who has to come out of his cave every so often to deal with the aftermath.

GamesBeat: What definition of the metaverse do you favor?

Stephenson: It’s gotta have a lot of people running around it. It has to have a large social component. I think it has to have a unified geography. This goes to rule number one of Tony Parisi’s rules. There’s only one. We need a kind of unified geography to it, or else everything decoheres after a while. I don’t think it has to do with any one particular output device or input device. Those are the key bullet points.

GamesBeat: It has some physicality to it, though, that’s interesting.

Stephenson: If you can just randomly hop around in no particular order, then what’s the point of denoting it as the metaverse or any other kind of verse? At that point it’s a bunch of 3D experiences that are hyperlinked to each other in some kind of random graph.

GamesBeat: But why is that not a metaverse, then? It is a digital experience.

Stephenson: That would be just like a 3D internet. On the internet there’s no geography to it. You can hyperlink from anywhere to anywhere and all links are the same. That’s just my one man’s opinion, I guess.

GamesBeat: You have a lot of technical knowledge. We can see that in your books. I came across a description of Alan Turing’s first computer in Cryptonomicon. How does this underpin your science fiction? What’s the relationship between science fiction and reality for you?

Stephenson: The first responsibility of a fiction writer is to get the audience to suspend their disbelief and immerse themselves in the story. Anything that pulls you in and helps you do that is good. Anything that makes you back away from it and stop believing in the story is bad. To a point, if you can include realistic-seeming details, it helps convey the sense that you’re describing a coherent world that makes sense and operates according to some kind of internal logic.

In the case of writing a science fiction book, that creates a place to make use of engineering knowledge or scientific knowledge, because, for example, in Seveneves, to name a particularly hard SF example, with a few exceptions I tried to base everything there on realistic orbital mechanics. Out of that came some unexpected details that wouldn’t have occurred to me if I had just been winging it and making everything up. I think if it’s used right, engineering details can add some feeling of verisimilitude to the work, and can also produce serendipitous results that give the writer ideas for things that might not have occurred to them otherwise.

Really the classic example is in Robert Heinlein’s book Have Space Suit, Will Travel. There are two people trying to escape across the moon wearing space suits. One of them is running out of air. They have to keep balancing the air between a couple of spare tanks. The threads don’t match, so they’re trying to improvise by putting tape around it. The tape is cracking and leaking. When I read that as a kid, it felt to me like, of course that would happen. Of course the threads wouldn’t match. It gave me the feeling that Heinlein had really been there and seen and done these things.

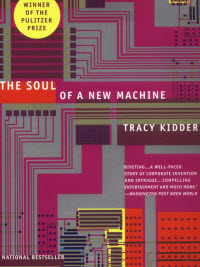

GamesBeat: I remember reading the Soul of a New Machine, and I got that feeling that I was there in the room between these competing teams that were trying to build mini-computers at the time.

Stephenson: Tracy Kidder’s book about the chip, the creation of that. A very powerful microchip, at the time.

GamesBeat: It makes you feel like a fly on the wall, witnessing these things.

Stephenson: It creates conflict. It creates obstacles that people have to think about and overcome. Again, if you don’t overdo it, I think it can work really well. You see it, too, in a lot of the technothriller genre. I remember reading one of the first Tom Clancy books back when it came out. You could almost see the moment he would pull out a 3” by 5” card and type in, “The F/A-18 Strike Eagle was a third-generation fighter produced by blah blah.” A whole bunch of statistical information and technical data about a fighter plane or something like that. On one level, if you’re viewing it from a literary fiction standpoint, it’s terrible, but from the point of view of what that audience wanted, it really drew them in and gave them a feeling that they were reading about something in the real world.

GamesBeat: Now that Snow Crash is about 30 years old, what does that make you think about now?

Stephenson: How old I am. This is the 30th anniversary year for Snow Crash. It came out in the summer of 1992. We’re coming out with a new edition, a new hardcover, in less than a month. Yeah, November 22, so I guess it is less than a month. Obviously there’s been a big upwelling of interest in the metaverse. We saw the M-word thrown around quite a bit during the last year. I think it was almost a year ago to the day that John Gaeta sent me a cryptic text message. I had no idea what it meant. John sent me a text message saying, “I’m sorry for your loss.” My first thought was he must have sent this to me in error. He must know somebody else who suffered a loss and he just typed in the wrong address. But then I got to thinking about it. I realized that maybe I’d better check the news. Sure enough, he was jokingly referring to the renaming of Facebook.

GamesBeat: Mark Zuckerberg renames Facebook as Meta. I guess it was nice of him not to rename it Metaverse.

Stephenson: I think it’s a word they use from time to time. But that’s okay.

GamesBeat: I did a Google trends search on the word in the public zeitgeist. It’s flat for 29 years, and then boom. It’s come down a bit, gone up again. It’s almost fashionable now to make fun of the metaverse.

Stephenson: Well, it’s the cycle of hype that happens with any technology. Beyond a certain point, people get tired of it and begin — at first it’s a badge of hipness to know what it is. Then a few months later it’s a badge of hipness to know that it’s tired and only lame people would be interested in it.

GamesBeat: It seems like it was momentous when Mark Zuckerberg did this. Is this about the same time you started thinking of doing your own startup?

Stephenson: I hadn’t really thought about it prior to then. I wasn’t sure what I could add. I was reluctant — this has been happening for a while with technologies that are described in my books. It happened first with the Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer in The Diamond Age, where I started hearing from people saying, “Hey Neal, I’m building the Primer. Look at my project.” I would look at their projects and they were all very different. One person was viewing it as working on nanotechnology. Someone else was making digital paper. Someone else was making the software needed to create interactive educational content. They all had different takes on what it meant. I started to realize that for me to come out and officially bless any one of these projects might be a nice thing for whoever ran that project, but other people would feel as though they were now operating at a disadvantage, or that I was dissing their interpretation by leaving it out.

With metaverse, I had a similar reluctance. But the idea that emerged last winter in chatting about it with my co-founder Peter Vessenes was that if you go a level deeper and work instead on underlying infrastructure and the fabric that other people could build things on, then at that point I wouldn’t be blessing any one particular interpretation of what it was, because the idea would be to enable anyone to realize their personal version of it. That was how we came to that plan.

GamesBeat: But you did have a strong bias toward open source, openness in general, and not toward the closed systems, the walled gardens.

Stephenson: I’ve been talking for a long time with Jaron Lanier about this. In a lot of ways, what I’m doing now is an outgrowth of a project that he and I worked on late last year. We were writing an op-ed for a major newspaper about — it was about the business model of social media and how ostensibly free platforms are actually making money by harvesting your clicks and your labor and your data. The weird distortions that leads to in our society. We worked on that for quite a while, and then got turned down. It never got published. We kept developing it and sending it around. It still hasn’t been published. But some of the ideas that came out of that collaboration are informing Lamina1 today.

I’ll name two. One is the notion that economic transactions ought to be transparent. In social media platforms it’s hidden. It appears to be free, but there’s weird stuff going on behind the curtain. The other one is the notion that when people join together to contribute value to something, their contributions ought to be tracked, and there ought to be a way for people to get paid if what they’ve built, what they’ve collectively built, is worth something.

GamesBeat: There’s a hidden cost to free, and then you can maybe understand why you had this reaction when Meta got renamed.

Stephenson: My reaction at the time wasn’t particularly strong. It was more bemused than anything. My thought in the subsequent months was, “Okay, maybe this has put me in a position to help create something that will have value, that will achieve something in this space going forward.”

GamesBeat: Will Wright was here this morning. I remember talking to him in the early 2000s, I think, and he said that a dog-eared copy of Snow Crash is the business plan for every startup in Silicon Valley. I think he was referring to the era when Philip Rosedale started out with Second Life. That was one of the first big crazes. But I guess the question is, when you hear people say that the metaverse is already here, what do you think?

Stephenson: Well, everyone has their own idea as to what that might mean. What happened that I didn’t predict 30 years ago was that games happened. At the time I wrote Snow Crash, I had burned a bunch of money and time assembling a rig to do computer graphics. I had a Mac II with Transputer boards in it. I learned this weird language called Occam so I could program them. I learned RenderMan. I learned a lot about the state of 2D and 3D computer graphics as of 1990. I came to the conclusion that it had incredible potential as a medium, but that the hardware was just, at the time, punishingly expensive. It was hard to do anything with it.

I started asking myself what would have to happen for that kind of hardware to become as ubiquitous as televisions are. The way it happened with TV was that everyone wanted to watch I Love Lucy or the Ed Sullivan Show. It started with programming that drew people in, that was very popular. The more people bought TV sets, the more the cost came down. Screens got bigger. We got color TV and so on. So what could drive an equivalent uptake in the case of computer graphics hardware?

The metaverse was my conjecture as to what that might be. That came out in 1992, and it was really the next year that DOOM came out. I remember looking at it and just being shocked that someone had made a 3D space that worked on the hardware of that era. I wouldn’t have thought it was possible. The other thing that happened was the World Wide Web came out and created a demand from people wanting to use their computers not just to work with text documents and spreadsheets, but to be able to look at pictures and movies and so on. That’s what really drove the cost of graphics hardware down over the next couple of decades, to the point where practically anyone can have a very capable machine.

GamesBeat: Games drove Moore’s Law, and alarmingly now people say Moore’s Law is about to end or has ended.

Stephenson: I keep hearing that. I don’t know.

GamesBeat: We need some science fiction to fix this.

Stephenson: Oh, yeah. I guess games ended up being the true driver of that drop in the cost of hardware. It’s to the game industry that we owe the fact that we’re on the threshold of being able to assemble a credible metaverse.

GamesBeat: Do you think that maybe games lead the way to the metaverse still? Is there a limitation to that? Do they have to get something right?

Stephenson: If your idea of the metaverse is that it’s a very popular communications medium with millions of people participating, then there’s an obvious assumption built in that there are experiences you can have there that lots of people will enjoy having. That seems obvious to say, but if there’s nothing fun to do there, then people aren’t going to go there and it’s not going to succeed. Who knows how to make experiences in 3D environments that are fun and enjoyable to have? Well, it’s people who make games, people who know how to use the tool chain of the game industry, starting with the engines and then the feeder applications, Blender and Maya and what-have-you that create the assets. If there is going to be a metaverse, those are the people who will have to build it.

GamesBeat: In the white paper for Lamina1 you say you’re also interested in helping out more than games. Every industry could benefit from this. It’s not just a gaming focus for you.

Stephenson: To be clear, what I’m saying is that regardless of whether you’re building a game per se, or something else, you still need the skill set of game makers. I did a thing in April — I get invited to do a lot of things, but the New York Times Style section invited me to participate in a panel on the fashion of the metaverse. Normally I turn everything down, but this was so ridiculous that I said, “Okay, I have to do this.” I went to New York and sat there in a big auditorium at the Times headquarters on a stage with Vanessa Friedman, the Style editor there who organized this whole thing. Tommy Hilfiger and a woman named Anifa Mvuemba, a young woman who’s a fashion designer in DC.

We talked about this, and I thought I was going to have to be the explainer. I did not have to do much explaining, because Tommy and Anifa both knew a lot about this. It was obvious that they had been thinking about this really hard, and that they saw the metaverse as an important thing for the future of their brands. Are they going to make games? They might make games based on fashion. But probably not. They’re probably going to make some kind of retail store or some way to try on clothes and see what they look like and then click through to buy them. However, you can damn well bet that whatever they do build is going to be built on top of game engines, and that if it looks good, it will look good because of the R&D that’s gone into rendering and game engines in the last couple of decades.

GamesBeat: If you had to write Snow Crash again now and set it 20 years in the future, how different would it be?

Stephenson: I actually am writing some new kinds of story content in that IP universe. I find I don’t have to change a lot. It’s partly because in science fiction, you lay down certain rules early in the book, and then you try to observe those rules through to the end. There are certain things about the metaverse as described in the book that probably are not how people would do it today, but if you just say that this is the way it is, it still holds up.

I’ve thought a lot about the rise of social media and how it seems to contribute to the fragmentation of society. On one level I didn’t see that coming. I kind of missed it. On the other hand, there are these people in the book who’ve had their brains taken over by this mind virus. They’ve been reduced to babbling idiots who are easily manipulated, easily led to doing bad things. That does sound kind of familiar. I might have inflected that a bit differently had I known social media was coming.

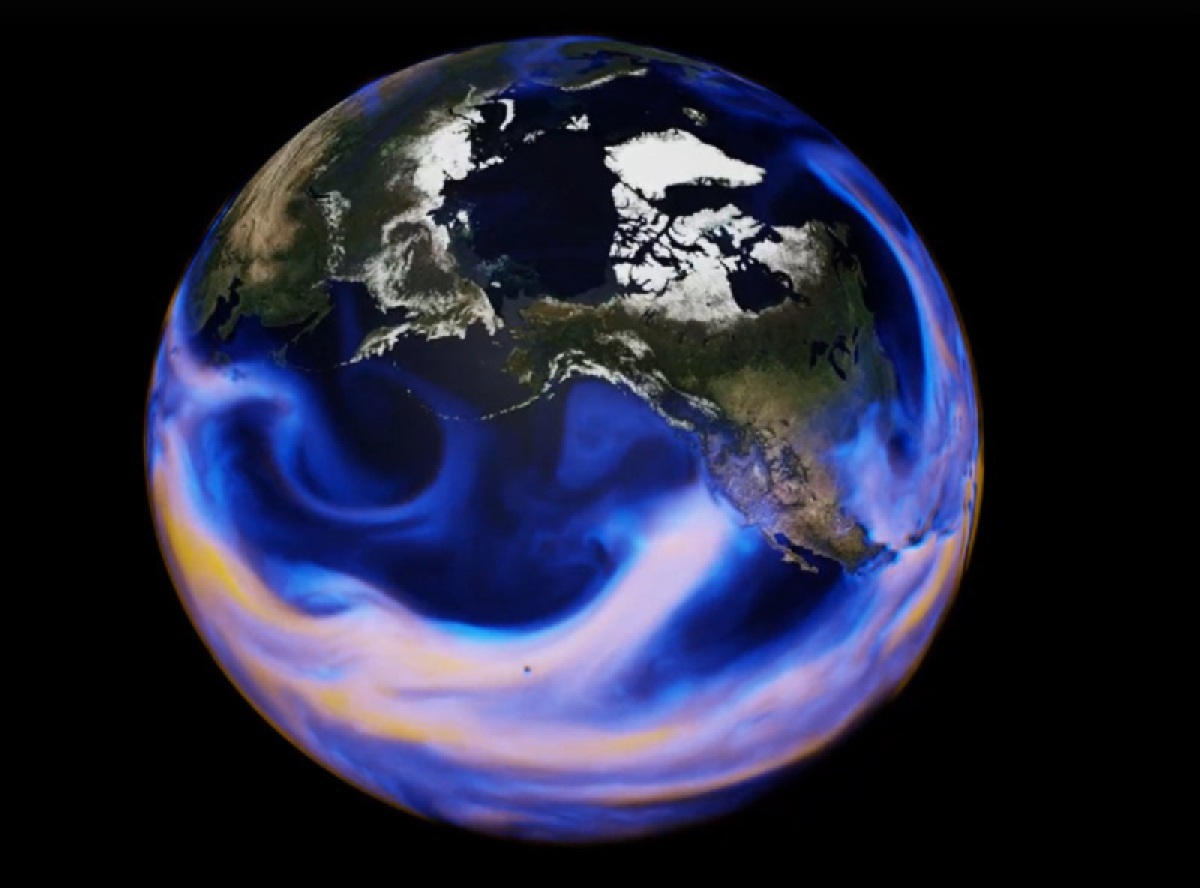

GamesBeat: I read Termination Shock, your newest one about climate change. It has some very interesting ideas in it. I had the goofy idea lately that — first, Brendan Greene, the guy who created battle royale and PUBG, he’s been saying he wants to build an entire world the size of the earth. That’s his next game. He just wants to let that loose and let people play in it. He would create that through things like game development, user-generated content, and AI. If people want to bring things from other worlds into the world, he can translate them with AI at the border.

Stephenson: He’s going to somehow automate the process of converting that asset into one that’s compatible with his world. That’s an interesting idea.

GamesBeat: Nvidia is doing Omniverse. Their CEO, Jensen Huang, I had a chance to ask him about this. He said that what they’re doing would also generate the metaverse for free. They’re trying to gather all the supercomputers of the world to create a digital twin of the earth and then predict climate change for decades to come. Earth 2. Once they’re done with Earth 2, can they just hand it over and say, “Here, you can use this world?”

Stephenson: Those two could get together and have a fully simulated realistic climate. Climate simulations are something that I did some looking into when I was working on Termination Shock. Obviously they’re famously computationally expensive to do. From what I understand, Nvidia has some ideas about using AI to route around the usual technical challenges. Normally you have to divide the atmosphere up into little cells and do computation on what happens at the boundaries between the cells. They have some way of using AI to get around that and make these things apparently run a lot faster. I’ll be super interested to hear about what they come up with.

GamesBeat: The other thing that maybe worries me about that — we’re leaving it all up to AI to do the hard stuff. If AI works that way, then great, it can do it. But it’s almost like believing in magic. We can’t do it ourselves, so let’s have AI do it for us.

Stephenson: It depends a lot on what field you’re working in. My theory of art is that a work of art consists of a huge number of micro-decisions that were made by an artist or a team of artists, and that when you experience that work of art, you’re communing with those people in a certain way. You can look at a Da Vinci painting and see the brush strokes. Each one of those is a decision that he made hundreds of years ago to dip a particular brush into a particular color of paint and move it a certain way. You can make similar statements about works of literature, movies, whatever.

If you’re looking at a work of art that was generated by an AI and you know it was generated by an AI, you don’t have that same feeling of being in a communion with a person or people making those decisions. I just think it’s different. But then in other areas, like climate simulation let’s say, maybe it works. It’s hard to know. You can run a climate simulator on past data and see if it accurately predicts what happened. I assume that’s how they calibrate their systems. If it works, it works.

Question: My son is 12, and there’s a hot topic when it comes to your catalog of, where do you start? If you were 12, what is the first book to start reading?

Stephenson: It depends a bit on some of your opinions about parenting. There is some pretty R-rated stuff in Snow Crash, some in Diamond Age. I would think Seveneves. Maybe Termination Shock. Depending on what they’re interested in.

Question: Your original envisioning of the metaverse and what it is now, how integral is blockchain technology and NFTs and cryptocurrencies, that discussion that’s going on — how integral is it to that vision now? Is it critical?

Stephenson: I have a somewhat biased point of view as co-founder of a metaverse blockchain company. I think, again, the key — there’s a lot of areas we could talk about with this. But again, I think the key thing that is needed to build the metaverse is to create a system where people who are good at building enjoyable experiences in 3D can expect to get paid if they make something that’s valuable. If you think through the details of what’s needed to put that into effect in a decentralized metaverse, the capabilities of blockchain are a pretty good match for what’s needed. With some tweaking and optimization I think that those two things can mesh pretty well. That’s what we’re working on.

In the metaverse we’re going to see both fiat currency and cryptocurrency. That’s how it works in the real world, so why shouldn’t it work in the metaverse? People will find the right solution to whatever problem they’re trying to solve. If we do our jobs right, a lot of those people will end up seeing the benefits of using a blockchain-based system for what they want to do.

Question: You mentioned the Primer earlier. You said that everybody had their own interpretation of it. I’m curious, what is it to you? Do you think it’s potentially closer to being possible with some things like large language models? And how might that change education in the world generally?

Stephenson: I do think it’s a little curious that we haven’t seen more in the way of personalized education. I don’t quite understand why. It seems like everything is there that we would need to make it work. Obviously there have been various projects like One Laptop Per Child, which stands out as a worthy effort to do that, but we’re still not, that I know of, seeing the vision that’s in the book, which is — based on what the book observes about the student, their style of learning, what they need to know, what works for them pedagogically, it feeds them pedagogical material that’s optimized for them. Maybe that’s happening and I just haven’t heard about it.

Some of it, I think, has to do with what happened with search engines, where in the early days of Google or whatever, if you googled for the Pythagorean theorem, you would probably see a reputable article describing the Pythagorean theorem, but if you do it today, you’ll get a few pages of sponsored content, people trying to sell you math lessons. Everyone’s gaming the system in a way that I don’t think is helpful.

Question: With the metaverse, you’re saying something about distance, or that it has to be — without having some concept of travel or something along those lines, you feel like it’s not going to be a metaverse? Could you explain that a bit more?

Stephenson: I kind of think so. Otherwise it’s just a bunch of experiences that are randomly linked to each other. It’s hard to conceptualize that as a space. I always thought — and this is just me talking as a guy who wrote a book 30 years ago — but for me it needed to have a particular geography to it. Things needed to be in particular places. If things are in particular places, they have a relationship to each other. You need to travel through space to get from point A to point B.

Now, I think you have to be able to teleport or to move at great speeds, or else it’s just going to be incredibly tedious to move around. But there are ways to calibrate that so that — I play a lot of Valheim. There’s teleportation. You can build portals in Valheim and go from one place to a specific other place. There’s a bit of a time delay, a few seconds long, so you’re not just popping from one place to another, which I think would destroy the feeling that you’re in a real space. But the fact that you have to spend 10 seconds looking at a swirly pattern on your screen reinforces the idea that you’re moving from one location to another location. To me, and this may just be me being sentimental, I think that some kind of overarching geography is needed to tie it all together and enable us to call it the metaverse.

GamesBeat: And we can sell virtual real estate this way.

Stephenson: Well, yeah. I think there should be a lot of virtual real estate. I mean, to the point where it’s not scarce, let’s put it that way.

Question: Xi Jinping is being elected into a third term. I’m sure you all know that basically the People’s Republic of China is not very good about protecting rights of individuals in the country. Are there areas where, now, compared to 30 years ago, you’re more worried about freedom of thought, freedom of speech and so on, individual liberties? And second, we all saw Mark Zuckerberg at some point going to Congress and legislators asking him how Facebook makes money. There is such a huge digital illiteracy within Congress and lawmakers. Is Lamina1 doing anything to help move American policy into the future? Are you involved in that?

Stephenson: Number one, am I more worried? I think I’m about the same worried. It’s just I’m worried about different stuff. I read a lot of history. Nothing is new. If you read the history of relationships between Russia and Ukraine, what we see now is a pattern that goes way back. It manifests in different ways at different times. In terms of social mission at Lamina1, it’s a new company. Our main emphasis in terms of taking an ethical stance on something has to do with carbon. We intend for this to be a carbon-negative chain. We’re working on building that into the staking system. The idea of promoting digital literacy is a new one to me, and so we’re not working on that right now. But it’s an interesting thought that I’ll take under consideration.

Question: Intellectual property is a plot device in a lot of your books. How do you imagine intellectual property in a creative post-scarcity economy that’s enabled by things like generative AI? Do these regulations become obsolete in terms of a consensus created by users of these systems? Do we need to reform these systems?

Stephenson: Of how we manage intellectual property? We’ve been talking about this a lot internally. My co-founder Peter Vessenes has a paper that I hope will be released soon about — in these generative art programs, can you track the contributions made by different artists to a particular outcome? He’s been doing some work suggesting that it’s quite possible to do that. The next problem becomes, is there a way to compensate people whose artwork got used, got consumed and used by the AI? In principle it seems like that should be possible. It’s one of these things that I think a properly engineered blockchain could do better than a fiat currency system. That’s rolled into what we’re thinking about there.

More generally, it’s just in the nature of a metaverse that you’re seeing — if you think about a video game, typically a video game is made by one company that owns all the IP, hires all the people to build the assets, do the programming, make the game. Out of that comes a particular kind of payment structure. In the case of a system where you have interoperability and people are taking assets from one experience to another, then that all gets muddled. It’s very hard to track that using the conventional systems of contracts and accounting and payments and all of that. That’s an example of something where some innovation needs to happen if it’s going to work.

Question: As large language models become more and more robust with GPT-3, GPT-4, and eventually GPT-5, what are your thoughts about OpenAI’s development and getting closer to AGI? What would that look like in the context of the metaverse?

Stephenson: Well, big question.

GamesBeat: Artificial general intelligence, basically something smarter than us.

Stephenson: I’ve done enough playing around with GPT-3 to have a sense of what it does. It can be amazing. It can generate incredible stuff. It can generate gibberish sometimes. But I’m sure it will get better as time goes on. The most interesting thing I’ve seen lately related to your question is what they’re doing at Inworld AI, using AI to make non-player characters that — we’ve all had the experience in Skyrim or whatever of having these stilted conversations with a face on the screen. There’s even amazing YouTube videos of people who’ve taught themselves to mimic the facial expressions and gestures of those characters. That’s something that’s needed improvement for a while, and what those people are doing has the potential to change the way virtual immersive environments feel. We’re going to see them populated by NPCs that are moving and interacting and talking in a somewhat more convincing way.

Question: There’s a thought out there that in our rush to build metaverses, virtual worlds, whatever we want to call them, we’re ignoring some questions in the real world, whether climate change or income inequality and what have you. Do you agree with that, or do you believe that building virtual worlds helps us solve questions in the real world?

Stephenson: It’s a tool that you can use to do what you want to do with it. If all you want to do is escape and goof off, then sure, that’s what you’ll do and it doesn’t have any social upside to it. Our experience has been that people get most engaged and most interested in talking about the metaverse when it’s tied to solving some problems, particularly with climate change, that are on people’s minds. I think most people have enough awareness of what’s going on in the real world and some of the problems that need to be solved that they’re actually somewhat turned off by purely escapist material, and excited by something that seems to have some relevance. I may be overly optimistic in saying that, but that’s been the sense we’ve gotten in talking about this in the last few months.

Question: You were talking about these ubiquitous and interoperable geographic spheres, ideally. Do you see a threshold in that in terms of social and political impact? In the last few months I’ve seen a lot of articles come out, papers and essays from theoretical and sociological thought leaders, Slavoj Zizek and Balaji Srinavasan, about these digital nations. I was wondering if you thought that we had the potential, once we escaped these geographical constraints that the real world presents — could we have this sort of digital escape velocity in terms of making impact on actual political decisions in the metaverse?

Stephenson: Political decisions relating to existing countries and policies, as opposed to just purely fictional. I guess my thinking about your question is just massively influenced by Ukraine and what’s been going on there. Seeing how the Ukrainians’ ability to show what’s happening and communicate with people in the rest of the world has transformed that war and made it unlike any other war we’ve seen in the past. The ability to communicate what’s going on and the extent of the tragedy, to see battles and skirmishes play out in real time on drone video, is a real game changer. I guess that’s maybe one data point suggesting that this can happen.

It’s one of these things where I expect and hope to be surprised. There are certain things that I’m pretty sure we’re going to see people building in the metaverse, and some things I want to build there. But with new technologies like this, what’s always most exciting is the stuff that you didn’t predict, the emergent stuff. I’m looking forward to being surprised as this goes forward.

Question: Dean asked for burning questions. What’s your favorite video game?

Stephenson: Valheim. Valheim, yeah. It’s beautiful. At first I liked it because I was all alone in this world, this very large world. I liked that. I don’t like massively multiplayer games where I’m constantly feeling stupid. I was able to feel stupid all alone for a long time, until I learned how to be reasonably good at the game. But then I discovered that a couple of people I used to work with at Magic Leap were playing a lot. I could tell by their tweets. I joined up with them and started a new server. Now it’s a social thing that I do a couple of times a week. I get together with these friends living in different parts of the world and we run around having stupid adventures together. We enjoy that experience.

A large part of it has become the social component. But also, it’s enough of an open world kind of simulation where weird, unexpected things happen. You get monsters bumbling into other monsters and fighting them. You can just stand back and watch ridiculous shit happening. I recommend it.

GamesBeat’s creed when covering the game industry is “where passion meets business.” What does this mean? We want to tell you how the news matters to you — not just as a decision-maker at a game studio, but also as a fan of games. Whether you read our articles, listen to our podcasts, or watch our videos, GamesBeat will help you learn about the industry and enjoy engaging with it. Discover our Briefings.