Solar-Powered Skyscrapers – A New Window Of Opportunity

Hi-tech glass coating lets light in and generates power

Solar windows are the future. Semi-transparent glass that generates energy from the sun could be commercially available within the next five years.

Technology is being developed today that could turn every pane of glass in a skyscraper into a floor-to-ceiling photovoltaic panel, providing an estimated sixth of the building’s electricity needs.

And it’s all thanks to advances in super-thin nano-coatings that allow some light to pass through, while turning the rest into energy.

The so-called third generation solar cells use a mineral called perovskite, which is cheaper, more efficient and more adaptable than the silicon currently used to coat almost every solar panel.

Prof Lioz Etgar, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has been a pioneer in the use of perovskite since its light-absorbing properties were first identified just over a decade ago.

He believes his research team are at the forefront of developing its potential and say they could be commercially available within “four to five years”.

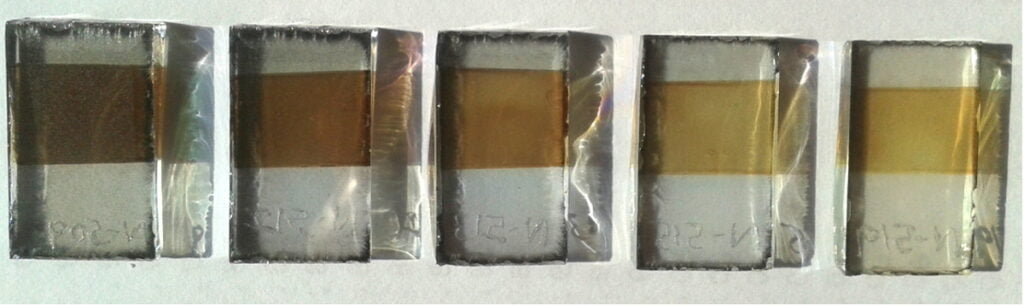

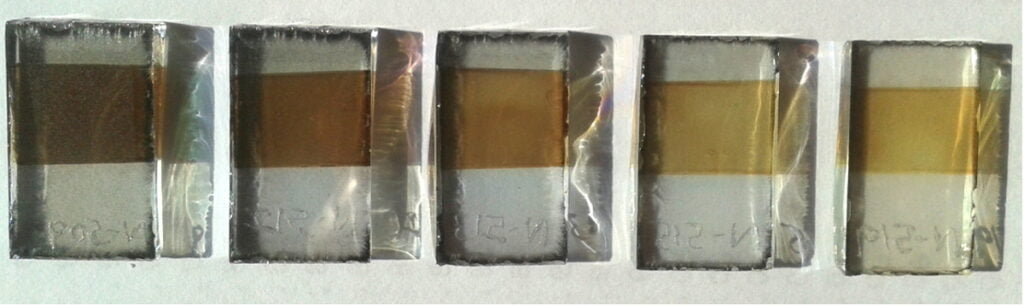

The sample solar windows they are working on currently are allow just over a quarter of the light to pass through, and are about two-thirds as efficient as ordinary panels.

He and his team are now competing with scientists across the world in the race to incorporate perovskite into full-sized windows.

Unlike traditional photovoltaic panels, solar windows still work even if they face away from the sun, so the plan would be to install them on all facades of a building.

“I was in my postdoc at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, in Lausanne, in 2012,” he tells NoCamels.

“During my last two months there, I was exposed to this new material. I tried it and it was amazing, really amazing.

“There were just groups of scientists around the world who had tried this material and we were one of them. Then I opened my own lab at the university and then I decided to concentrate fully on this material because I understood there was so much to discover about it.”

At present the team at Hebrew University is producing small prototypes, up to 20cm (8 inch) squares. The challenge is to scale things up at a commercial cost and to achieve maximum efficiency and transparency.

The team has spent the last seven years developing patented methods to fully exploit perovskite’s molecule structure and they’ve engineered nine different ultra-thin layers into a “printable ink” that will be used to coat the glass.

Prof Etgar says: “In my lab, we are able to synthesize the perovskite in many different and unique ways and to understand a lot of interesting properties.

Those investigations are already pointing towards two more ground-breaking opportunities. The first is “tuning” or synthesizing perovskite so that it creates energy from artificial light, as well as sunlight.

“That allows us to find unique applications. Also, more fundamentally, we are investigating the material itself, in terms of synthesizing it from a molecular level and understanding how nanoparticles – too small to see by eye – have different properties from larger particles of the same material.”

That means that in future the lightbulbs that illuminate indoor space could partly power the solar windows, which in turn would create some of the electricity that powers those same bulbs.

The second possible application is putting it on greenhouse roofs. Traditional solar panels would shade the plants from sunlight, but glass coated with perovskite, allows it to pass through.

To develop the solar windows technology, Prof Etgar recently co-founded a startup called Trans/Sol with fellow Hebrew University professor, Shlomo Magdassi, a specialist in materials science and nanotechnology.

Trans/Sol’s aim is to produce solar windows as a “curtain wall” – the non-structural outer covering of a building, usually made of glass, metal panels or thin stone.

“It will change the word forever,” says Guy Price, CEO at Trans/Sol. “Once we have solar glazing, the word will never go back to any normal glazing.

“In general buildings account for 36 per cent of the word’s carbon pollution. And in terms of new buildings, we are looking at adding the equivalent of an entire New York City to the world, every month, for the next 40 years.”

That’s why new buildings that generate their own power will make such a difference. “If we don’t make buildings that are efficient and produce their own energy, you know, from our perspective, we’ll never solve the pollution issue.

“The focus at this stage is upscaling the technology to window size. Then we’ll work with market leaders such as glass companies, curtain wall manufacturers, engineers and architects to create a system to be able to place it on buildings.”