Lithium extraction could be a boon for Alberta, but it comes with environmental uncertainties

The word mining conjures up visions of environmental destruction and ecosystem disruption, like mountain-top removal coal mining, or the surface mining in the Athabasca oil sands.

But lithium brine mining is quite different, at least as envisioned for Alberta’s still-undeveloped industry.

The provincial government and the private sector have for years framed it in green terms: an extractive industry that would generate profits and jobs, and help advance the global adoption of electric vehicles, all with minimal environmental impact.

Lithium extraction hasn’t arrived in Alberta yet, but it’s fast approaching, with the potential to become a significant industry. It’s worth understanding now.

The ol’ mine ‘n’ brine

The third-lightest element overall, lithium is a highly reactive alkali metal and relatively unstable. It never occurs by itself in nature, only in compounds.

It has a variety of uses, from greases to medication, but its most common use by far is in lithium-ion batteries, which are critical for many consumer devices, but especially for electric vehicles.

The current methods for producing lithium can be divided into two categories: traditional dig-a-hole-and-blow-up-rocks mining, and brine mining.

Proponents say Alberta is well-set to capitalize on rising lithium prices, but first, the province needs to set regulations around its extraction.

The first type is self-explanatory, and is typically catastrophically disruptive to local environments. This is how Australia — the leading producer, providing nearly half of the global total — gets much of its lithium.

One of the few lithium mines in North America, in an open pit 550 kilometres northwest of Montreal, is planning to reopen early next year.

But minerals aren’t just found in rocks. They’re also found in very salty water known as brines.

Some of these brines have fairly high concentrations of lithium and are found under expansive salt flats in the “Lithium Triangle” of Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. Chile alone holds 40 per cent of the world’s lithium.

By comparison, Canada holds 2.5 per cent.

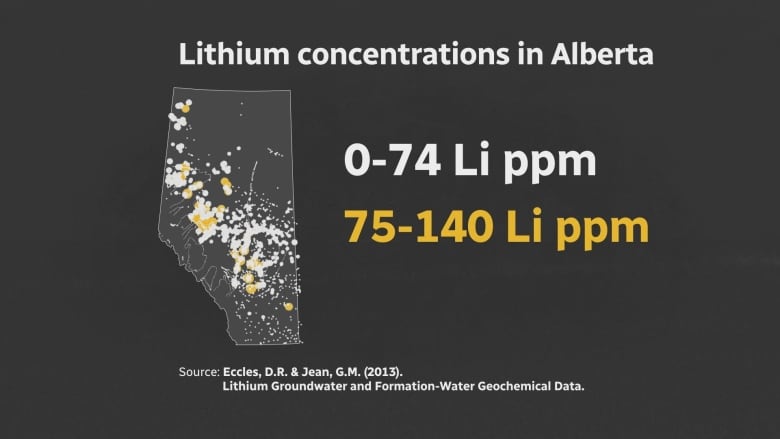

Alberta’s brines have lower concentrations of lithium and are found deeper underground in sedimentary basins. Historically, these brines were never seen as an economically viable source of lithium — it’s easier and cheaper to mine it from rocks in Australia, or pump up shallow brine to be evaporated under the South American sun.

But with surging demand for lithium-ion batteries, interest in unconventional sources began to grow. When the price of lithium skyrocketed in 2021, Alberta’s prehistoric brines went from probably economically viable to a potential — for lack of a better phrase — gold mine.

“Those have potentially become economical if we can get an extraction technology that can recover this lithium, upgrade it, turn it into the salts that can manufacture batteries,” says Dan Alessi, a professor at the University of Alberta and co-founder of Recion Technologies, a company that develops just such extraction technologies.

The impact of lithium extraction

Alberta’s advantage, according to proponents of a would-be lithium extraction industry, is the existing oil and gas wells, the infrastructure, the expertise, and a workforce with transferable skills to enable us to harvest our brines with modest concentrations of lithium without significant environmental impact.

Albertans, after all, have been pulling brine out of the ground for decades. We’ve just been throwing it away.

“Almost always when you produce oil and gas, you produce wastewater brine as a byproduct,” says Alessi.

“Typically what’s been done with this, it’s stored at the surface, transported to a different location, and it’s reinjected into another aquifer.”

Contrasted with the practice in the Lithium Triangle of letting the brine evaporate for more than a year, the Alberta brine would be put back into the ground once relieved of its lithium. This, proponents say, means far less impact on aquifers, and little or no use of freshwater.

Lithium mining from brine has been held up by business and government as an environmentally responsible new industry for Alberta. And, in comparative terms and on paper, it certainly appears that it would be far less damaging than how lithium is sourced elsewhere, or for that matter some of our other local extractive industries, such as surface mining in the Athabasca oil sands or coal mining.

But no resource extraction comes without impact. And it is hard to anticipate all the potential ways brine mining could affect local ecosystems, given that these methods are not being used at scale anywhere in the world.

A December 2021 policy paper from the Smart Prosperity Institute and Energy Futures Lab cautioned that, “While lithium brine extraction has significant downstream environmental benefits compared to oil and gas extraction, it would likely have similar upstream environmental costs, including damage to land, air and water and carbon-intensive extraction processes.”

The authors suggested that an Alberta lithium industry could benefit from the environmental mitigation expertise of the fossil fuel industry.

Christopher Smith, a conservation analyst with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society’s Northern Alberta chapter, is struck by the many uncertainties around the methods of lithium extraction being proposed in Alberta.

“Because this is all so new, it’s been challenging finding actual quality information on what are the environmental impacts and what are the opportunities and risks associated with this, because it really hasn’t been done in any jurisdictions that I can find,” he said.

“The downside is, because this type of extraction hasn’t really happened at scale in any other jurisdictions, it’s hard to know how exactly it’s going to roll out.”

Understanding the brine process

In comparative terms, brine mining is certainly far less damaging to the environment than many of Alberta’s other resource extraction industries. Unlike strip mining for coal, it doesn’t require catastrophic disruption of earth and ecosystems.

And it doesn’t come with long-term destructive legacies on the scale of the tailings ponds in the oil sands or scores of abandoned wells.

No resource extraction comes without a cost, and not just the monetary investment.

But Chris Doornbos, founder and CEO of Calgary-based E3 Lithium, says the chance of unforeseen environmental impact is “pretty low.”

“The processes that we’re all using fall under the general realm of an ion exchange,” he says. “An ion exchange is, in and of itself, very well understood. The water softener in your house is an ion exchange system.”

Even the small environmental footprint of E3 Lithium’s proposed extraction process is something Doornbos wants to improve upon.

He mentions “social licence” as a key part of the attractiveness of an Alberta lithium industry, adding that car companies, especially in Europe, are taxed based on the carbon footprint of the materials they source — potentially giving lower-impact lithium extraction an edge in the market.

Oversight concerns

The provincial government under the UCP has made mineral extraction a priority, establishing a Mineral Advisory Council, and passing the Mines and Minerals Act in 2020 and the Mineral Resource Development Act in 2021.

The latter legislation established the Alberta Energy Regulator as the lead authority for mineral resources, streamlining oversight with an eye to encouraging private development.

But a new permit regime for mining minerals from brines is supposedly coming soon — Doornbos says he’s seen drafts, but can’t discuss the details — that would take brine mining out of the set of regulations applicable to traditional forms of mineral mining.

“What we’re doing is more in tune with oil and gas production than conventional mining,” says Doornbos.

Neither set of rules fits brine mining perfectly, but in his opinion, “the closer one is oil and gas.”

Alberta Energy did not respond to multiple requests for an interview with newly installed minister Pete Guthrie, instead forwarding requests for a statement to Alberta Environment and Protected Areas — whose minister, Sonya Savage, previously held the energy portfolio.

“When it comes to brine-hosted resource development for the lithium industry in Alberta, government anticipates this will be similar to the oil and gas industry,” said Savage’s press secretary, Miguel Racin, in a statement.

“We are working closely with the Alberta Energy Regulator to ensure there are regulatory requirements in place to manage the environmental considerations unique to this emerging industry.”

Smith, with CPAWS, points out that under existing regulations, lithium projects would not automatically receive an environmental assessment, something he finds concerning.

“We’ve seen time and time again, a new industry develops, we’re very quick to develop the rules and regulations, and it’s only later in hindsight we realize that maybe we moved a little too quickly and perhaps didn’t look at the consequences of these activities closely enough.”

Staking their claim

At present, no one is extracting lithium from brine in Alberta. But a handful of firms are poised to do so.

LithiumBank, a Vancouver-based firm, owns two projects in northwestern Alberta, which they renamed from Sturgeon Lake and Fox Creek to Boardwalk and Park Place, respectively.

E3 Lithium has acquired a significant foothold in lithium-rich areas. The company has partnered with Imperial Oil to extract lithium from the brine beneath Leduc No. 1, the oil well that set off Alberta’s first oil boom in 1947.

Summit Nanotech, based in Calgary, has plans to use nanotechnology-based sorbents elsewhere in the world, while keeping an eye on the Alberta market.

These and other companies have popped up and grown in recent years as the combination of a high price, high projected future demand, and buzz around the role of lithium in a net-zero future has attracted a lot of investment attention, according to Doornbos.

“When there’s a lot of excitement around a commodity, like lithium, people are more willing to put more high-risk capital towards it.”

But there’s no telling what the future may hold. A potential curveball could be that, with tremendous resources being poured into research, a long-sought breakthrough in new battery technology appears that doesn’t require lithium.

And while making use of existing oil and gas wells is low hanging fruit, it’s easy to imagine a successful lithium industry seeking to drill new wells at some point, widening its impact. After all, Alberta’s oil industry began with conventional crude — hardly a green industry, but far less impactful than extraction in the oil sands, which was only enabled decades later with shifting markets.

“We don’t want what happened with oil and gas to happen with lithium, in that if lithium prices crash and a bunch of the smaller players go out of business, are we going to be left with a bunch of lithium extraction wells?” says Smith.

The supposedly green nature of electric vehicles has also been questioned, as the production of new personal automobiles is carbon-intensive regardless of its fuel type.

Demand for lithium, however, is not likely to drop any time soon, and the companies looking to build an industry in Alberta will continue, with the support of government, to forge ahead.