Ever since its launch in July 2021, a Purdue University-affiliated initiative has been ramping up its efforts toward an ambitious goal: helping to ensure that technology is used in ways that advance democracy.

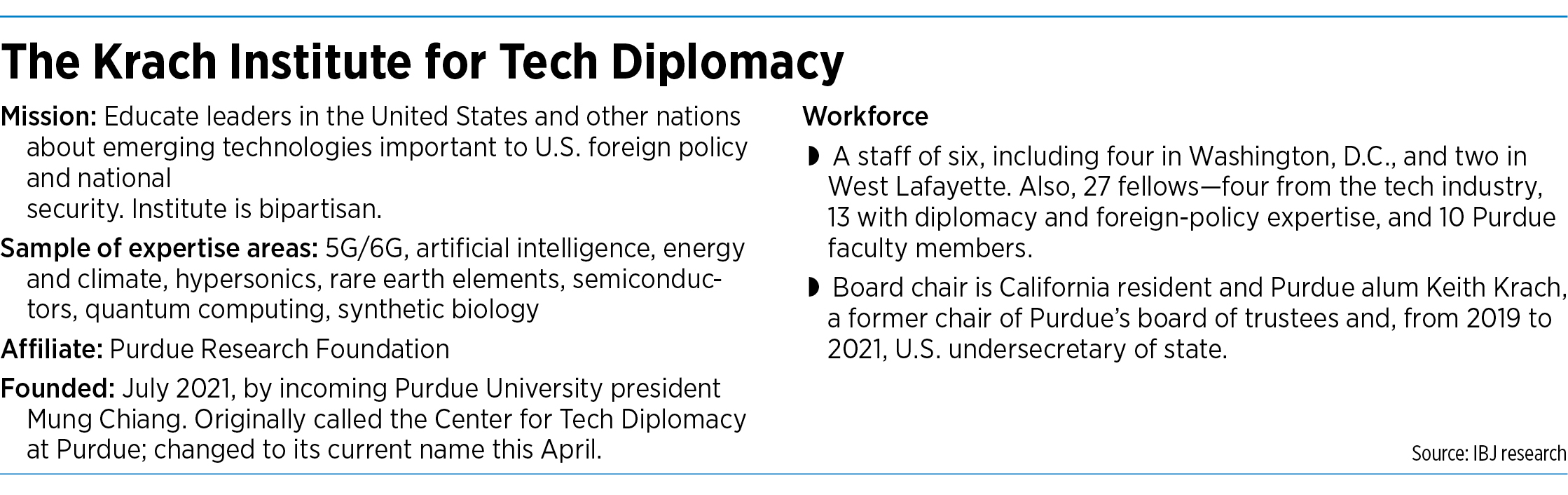

The Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue, which is part of the university-affiliated Purdue Research Foundation, aims to educate policymakers, diplomats and others about artificial intelligence, semiconductors, quantum computing and other technologies relevant to national security and U.S. foreign policy.

The institute wants technology to be developed and used in ways that advance freedom and democracy, rather than authoritarianism.

“This is really a long-term challenge,” said the Krach Institute’s director, Michelle Giuda, who joined the institute in October. Giuda comes from a background in communications, politics and government, including serving as assistant secretary of state for global public affairs at the U.S. Department of State from 2018-2020.

“The stakes right now are as high as they can get,” Giuda said. “If we want to advance freedom, we have to secure technology.”

To that end, over the past 17 months, the institute has:

◗ Built a staff of six employees, with offices in Washington, D.C., and West Lafayette.

◗ Assembled a team of 27 fellows, including 10 Purdue University professors, with experience in diplomacy, foreign policy and technology.

◗ Participated in an event in September that brought U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo to Purdue’s campus to tour its nanotechnology center.

◗ Hosted a series of technology information sessions for legislators and diplomats.

◗ Formed a China-focused partnership with the Atlantic Council, a nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

Incoming Purdue president Mung Chiang, who took a leave from the university in 2020 to serve as science and technology adviser to U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, founded the institute. It was originally known as the Center for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue, before being renamed in April for its board chair and former Purdue University board chair Keith Krach. Krach also worked as an undersecretary of state in the State Department, from 2019 to 2021.

A group of institutions, individuals and corporations provided $60 million in seed funding for the institute. Former U.S. Secretary of Defense and former Central Intelligence Agency Director Leon Panetta, retired Gen. Stanley McChrystal and former U.S. Rep. Susan Brooks are among the institute’s board members.

A focus on China

One of the Krach Institute’s major areas of focus right now is its partnership with the Atlantic Council.

In May, the two organizations formed the Global Tech Security Commission. The commission’s goal is to compose a set of standards for the development and use of key technologies and to promote the adoption of these standards in the United States and abroad as a way to counter authoritarian use of these technologies, particularly in China.

“It’s a pretty ambitious undertaking,” said Colleen Cottle, deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub.

One of the technologies the partnership will examine, for instance, is artificial intelligence.

“It’s such a new technology, there aren’t global standards for how you should morally, ethically be using this technology,” Cottle said.

If a law enforcement agency in a Western country uses artificial-intelligence-powered surveillance tools, she said, it is limited by factors like admissibility of evidence in court and privacy laws. But those rules aren’t in place in China, she said, where the government conducts surveillance on its own population.

So the standards the Krach Institute and Atlantic Council come up with will take into account considerations like human rights, transparency, the rule of law and the environment.

The partnership also will develop similar standards for other key technologies—like 5G, clean energy and electric vehicles—putting it all in a report due next spring.

Once the standards are written, Cottle said, the goal is to get countries around the world to adopt them. Ultimately, the partnership hopes to shape China’s behavior with regard to technology and to curtail the nation’s access to high-tech components, research and talent.

“It’s very ambitious … and some of it’s a little theoretical, almost,” she said. “We haven’t solved how to do this yet, as Chinese companies and government-supported research institutions continue to move up the value chain.”

Looking forward

The Krach Institute has already tackled some more immediate and tangible tasks, including holding informational sessions on specific tech topics.

Senior Research Fellow Dan DeLaurentis is a professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Purdue. His expertise is in hypersonics, which refers to speeds that are at least five times faster than the speed of sound.

In January, DeLaurentis traveled to Washington, D.C., to lead a hypersonics workshop for a group of diplomats and congressional staffers.

Among the topics DeLaurentis covered were the definition of hypersonics and why it’s more difficult to detect and defend against hypersonic weapons. (Short answer: Because they’re so fast.)

The topic became directly relevant a few months later, DeLaurentis said, when reports emerged that Russia had used hypersonic missiles against Ukraine. In a situation like this, diplomats who know something about hypersonics are better equipped to do their jobs.

“It’s just being ready to take that next-step conversation when it’s needed,” he said. “At the pace that things happen in our world today, that could actually make a difference.”

DeLaurentis said he’s not aware of any other organizations tackling tech diplomacy in exactly the way the Krach Institute is. What makes the institute different, he said, is that it is looking not just at the current state of technology, but also at where the technology might be headed.

“You rarely see an organization that truly has the cutting-edge technology leaders,” he added.

Growth of tech diplomacy

The Krach Institute is among a growing number of entities tackling tech diplomacy.

The State Department—where Krach, Chiang and Giuda formerly worked—has focused on tech diplomacy for years, said the department’s acting science and technology adviser, Allison Schwier.

Schwier said the State Department has also participated in some of the Krach Institute’s programs.

And recently the national security advisor identified three groups of technology of particular importance: computing-related technologies, like microelectronics, quantum information science, artificial intelligence; biotechnologies and biomanufacturing; and clean-energy technologies.

“Today, the State Department is working with like-minded partners and allies to promote the promise these technologies hold while protecting against their abuse,” Schwier said in an email to IBJ.

Other entities have also been working to advance tech diplomacy.

In 2017, for instance, Denmark became the first nation to appoint an ambassador dedicated to technology issues.

Denmark’s current tech ambassador, Anne Marie Engtoft Larsen, is based in Palo Alto, California. She spends about half her time interacting with technology companies of various sizes, both in the U.S. and abroad. She spends the other half interacting with foreign governments, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, and with organizations, such as the United Nations, universities and human-rights groups.

“There’s so much happening that requires dialogue—and that’s diplomacy,” Larsen said.

“The future of war, the future of peace is so dependent on technology,” she said.

The diplomat said much of her job involves building lawmakers’ confidence about their ability to understand technology.

“You don’t need to be a software engineer to have a quite nuanced understanding of how you need to tackle issues around artificial intelligence—and the potential pitfalls and how to regulate outcome and expectations, and the impact it has on society,” Larsen said. “… The same goes for almost any technology, and that’s what we help with.”

Since Denmark established its tech ambassador, Larsen said, about 35 countries around the world, including the U.S., have followed suit, and a growing number of universities are launching efforts around technology and policy,as well.

In September, Nathaniel Fick was sworn in as the United States’ first-ever ambassador at large for cyberspace and digital policy.

That same month, the European Union opened an office in San Francisco to advance the organization’s digital diplomacy efforts with the United States.•