The Future of Memory

As memory and data blur, will we remember everything? And does remembering everything mean remembering nothing?

“The root of men’s problems is memory,” states martial artist Huang Yaoshi, a character in Wong Kar-wai’s arthouse classic Ashes of Time (1994). The film revolves around the dialectics of remembering and forgetting; in it an anonymous desert’s shifting sandscape suggests a geological palimpsest of writing and unwriting memory at the same time. In the age of information saturation, people are entangled in the present technoscape of an attention economy that keeps altering.

In Lawrence Lek’s ongoing ‘episodic virtual world’ Nepenthe Valley (2022–), ruins suturing ancient and futuristic architectural features are situated in a digital ‘natural’ landscape. Named after the Ancient Greek (mythical) potion of forgetting, the project suggests the possibility of a therapeutic oblivion via game playing, exploring the ‘doorway effect’ – a psychological status under which one’s memory fades when passing from one place to another – in the liminal spaces between the virtual and the actual. The virtual ruins look uncannily strange-but-familiar and are contained by sublime, hilly simulations, forming spaces for mental walking, making it a mirror of Simonides’s method of loci (in which the Roman developed a system by which humans could store large amounts of data in their minds by linking the information to mental images of places).

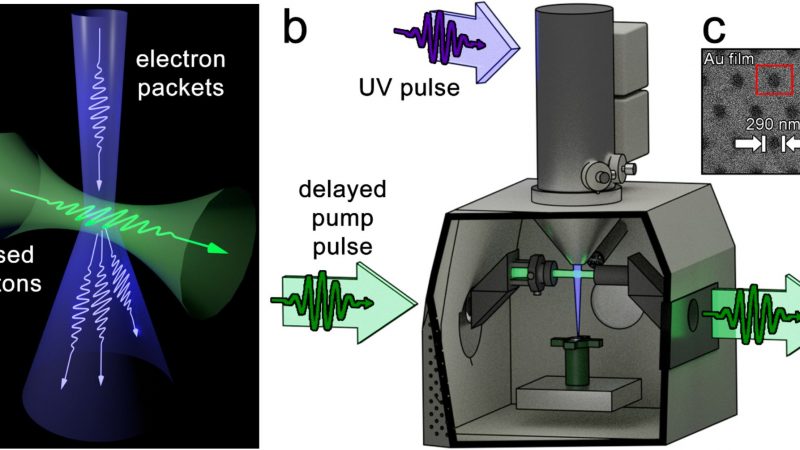

If Lek’s Nepenthe Valley is an experiment for a futuristic mnemonic mechanism, aaajiao’s Memory Vending Machine (2009) is a speculation on the futures of memory. Based on the artist’s research into current nanotechnology and biotechnology, the artwork is a fictional ‘invention’ – a gashapon (a popular vending machine selling capsule toys) with ‘manual’ videos presented on screens attached to the front of the dispenser explaining how this conceptual device works: the machines sell plastic balls containing ‘nanobots’, which are then introduced to one’s neurosystem via inhalation. The nanobots multiply and create new memory zones in the brains of the users (and memories then become exchangeable and transferable between the purchasers). On the surface, this sounds like pure sci-fi fantasy, but at the same time, it could also be a prophecy of our near future.

Already, limited human memory capacity may drive some people to externalise their memories to the Cloud (operated by a network of servers). If one sees memory as a neurochemical process and psychological ‘faculty’ for ‘encoding, storing and retrieving information’ (according to neuroscientist Larry Squire), then externalising memory to the Cloud provokes questions of memory authorship and revision, and how it remains a space of privacy.

Scientists are now racing to explore the possibilities of synthetic DNA as a medium for digital information storage. Nature magazine describes the technology as a combination of ‘DNA synthesis, DNA sequencing and an encoding and decoding algorithm’. Binary data is decoded and encoded in DNA’s four nucleotides. The technology might drastically condense and make durable memory storage: according to MIT News, ‘a coffee mug full of DNA’ could store all the current data in the world.

The technology may also herald a new round of technological and corporeal integration. Would it be possible, for example, to reinternalise (or ‘download’) massive amounts of externally stored memories and data into human bodies? Will there be a seamless brain implant for memories? (Farewell to Johnny Mnemonic-style headset devices!) When straddling the computer coding of the Cloud and the genetic coding of DNA, will there be a doorway effect in which we forget our bodies? And in that event, who or what would own those memories that migrate between the body and the servers that store that information? Who will have the right to edit, interpret, formalise and present memories in the future? If memories are stored in DNA – the old medium for biological information – and synchronised on multiple digital devices, what connects these sutured temporalities? And what, in fact, is memory in this case?

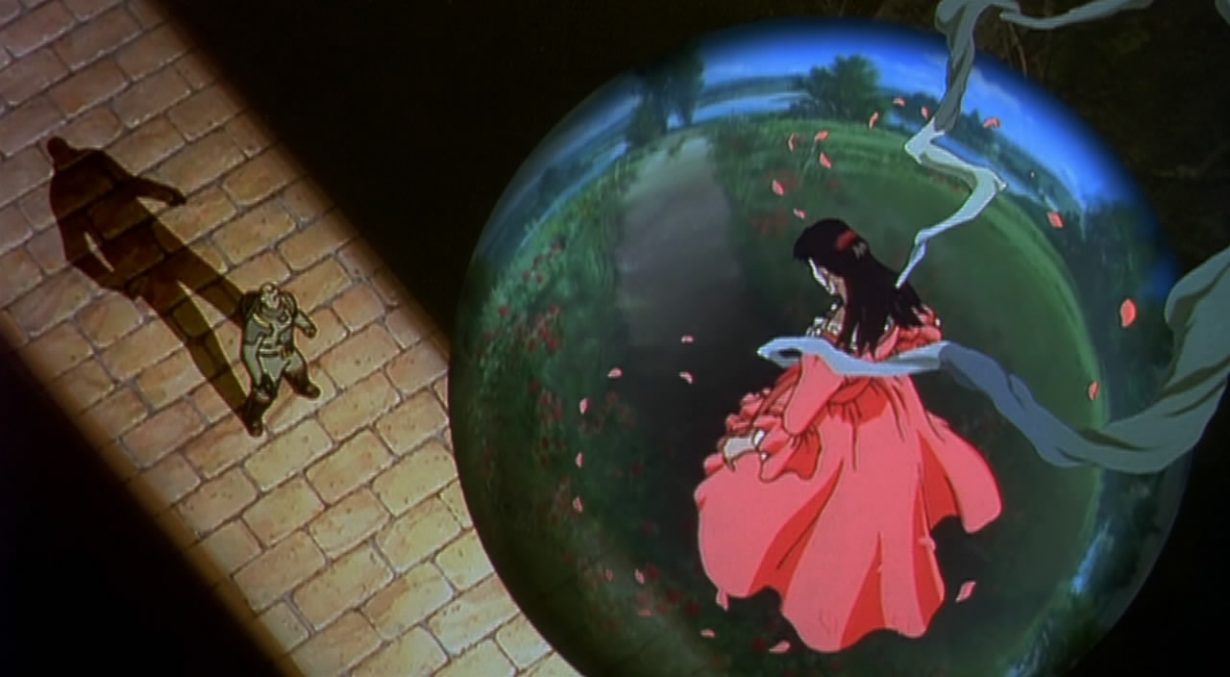

Futuristic conceptions of how memory functions abound in sci-fi. Magnetic Rose, a short animation directed by Koji Morimoto and scripted by Satoshi Kon, is the first part of Memories (1995), an anthology film produced by Katsuhiro Otomo based on his manga stories. Set in 2092, Magnetic Rose follows two engineers who work on a salvage freighter called Corona. Responding to a distress signal coming from an abandoned space station, the engineers find gravity, oxygen, opulent European interiors, holographic blue sky and white clouds outside the windows, and even a sumptuous feast laid out on a table. The engineers keep encountering the spectre of an opera diva named Eva Friedel, the long-dead owner of the station. As music from an aria in Madama Butterfly (1904) floats through the station, the two engineers (who have become separated) start to hallucinate: one sees his late child; the other falls in love with Eva and reenacts the romantic memories of the opera singer and her onetime fiancé. The hallucinations take the form of holograms and melting white sculptures resembling 3D-printed objects that embody the past personal memories of Eva and the engineers. It turns out that the haunting diva is in fact an AI robot ‘living’ Eva’s consciousness; Eva’s corporeal form is nothing but a skeleton.

Magnetic Rose recalls the plot of Stanisław Lem’s novel Solaris (1961), where the psychologist Kris Kelvin sees his dead wife in a space station – an embodiment of Kelvin’s shared memories with his spouse. But in Magnetic Rose the singer’s ‘apparition’ is the reification of the memories of a stranger, reformalised via technology into physical objects and entities; each character’s memories gravitate and intertwine with the others’ to generate seemingly ‘real’ experiences, and thus more ‘memories’. In the closing scene, Eva sings from a floating bubble, sirenlike, while the station’s powerful magnetic field starts to pull in and devour Corona and everything around it.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) similarly explores ideas around the exteriorisation of memory. David is a robotic AI child – a futuristic version of Pinocchio – who is able to love, and, having been abandoned by his human family, goes in search of the Blue Fairy (a character from The Adventures of Pinocchio, 1883), who he believes can turn him into a ‘real boy’. At the end of the film David is unsuccessful in his quest to find the Blue Fairy (who turns out to be a statue in an abandoned themepark), but is revived 2,000 years later, after his battery has been depleted, by a new generation of AI robots. By this time, humans are extinct and cities are buried beneath glaciers. The advanced androids read David’s memories and reconstruct his home, as well as clone his human ‘mother’ (or owner), Monica, from a strand of her hair. As a mass-manufactured machine, David is supposedly devoid of individuality – yet he does have ‘personal’ memories of his beloved mother. Are the recollections of David, who is a machine, just volatile memories? Or are they memories that construct his ‘consciousness’? A.I. not only rethinks the psychological mechanism of a nonhuman via an old fairytale, but also raises the question of how memories might be archived for the future. In both Magnetic Rose and A.I., memories bleed beyond the flesh. The recollection of undying love possesses and haunts both human and robotic bodies, and new memories are created and stored.

J.G. Ballard’s novel The Drowned World (1962), an early climate fiction, imagines the role of memory in the human and terrestrial sense – the wrestling between human memory and the geological memory of Earth. It is set in 2145, when most of the world’s landmass is underwater, and solar storms have weakened Earth’s ionosphere, causing rapid surges in temperature and sea levels. Wilderness takes over urbanscapes, ‘rekindling archaic memories of the terrifying jungle of the Paleocene’, while relics of the manmade world disintegrate and are forgotten (people don’t even remember where London is) as the wilderness builds up. Does a drowned world with giant mosquitoes and ferns represent a regressive or progressive future? While the former is compatible with a linear, anthropocentric temporality, a zero-sum game in which humanity’s ‘advancement’ is marked by the conquest of nature (and regression when nature fights back), the latter might resonate with the idea that Earth is an organ with its own will (and that this future is inevitable, regardless of human impact).

Wax tablets could be used as a metaphor for how memory works, emphasising the relationship between writing and recording, and the physical manifestation of the writing and recording. In Ted Chiang’s short sci-fi story ‘Exhalation’ (2008), the wax of the metaphorical tablet is replaced by flakes of gold leaf interwoven with air capillaries, whose patterns change as air flows through the brains of mechanical inhabitants made from titanium, and onto which the humanoid’s experiences are inscribed. Here, then, consciousness is merely a ‘pattern of airflow’. If our memories are also just patterns between neurons, and if the foreseen externalisation of them slowly blurs the boundaries between personal memories and all the data in the world, will we remember everything? And does remembering everything mean remembering nothing?

In the event of drastic future developments in our understanding of consciousness, neuroscience and time, when the gaps between our internal and externalised memories narrow or even seal up, will we forget ourselves? And will we reinvent again and again ways to encode memories, like Funes in Borges’s ‘Funes the Memorious’ (1954)?

Translated from the Chinese by Claire Li