The global microchip race: Europe’s bid to catch up

On the edge of a tranquil forest an hour’s drive from Stuttgart, where hiking trails snake through the trees and across gently rolling hills, sits one of Europe’s secret weapons in the global race to develop the world’s most advanced semiconductors.

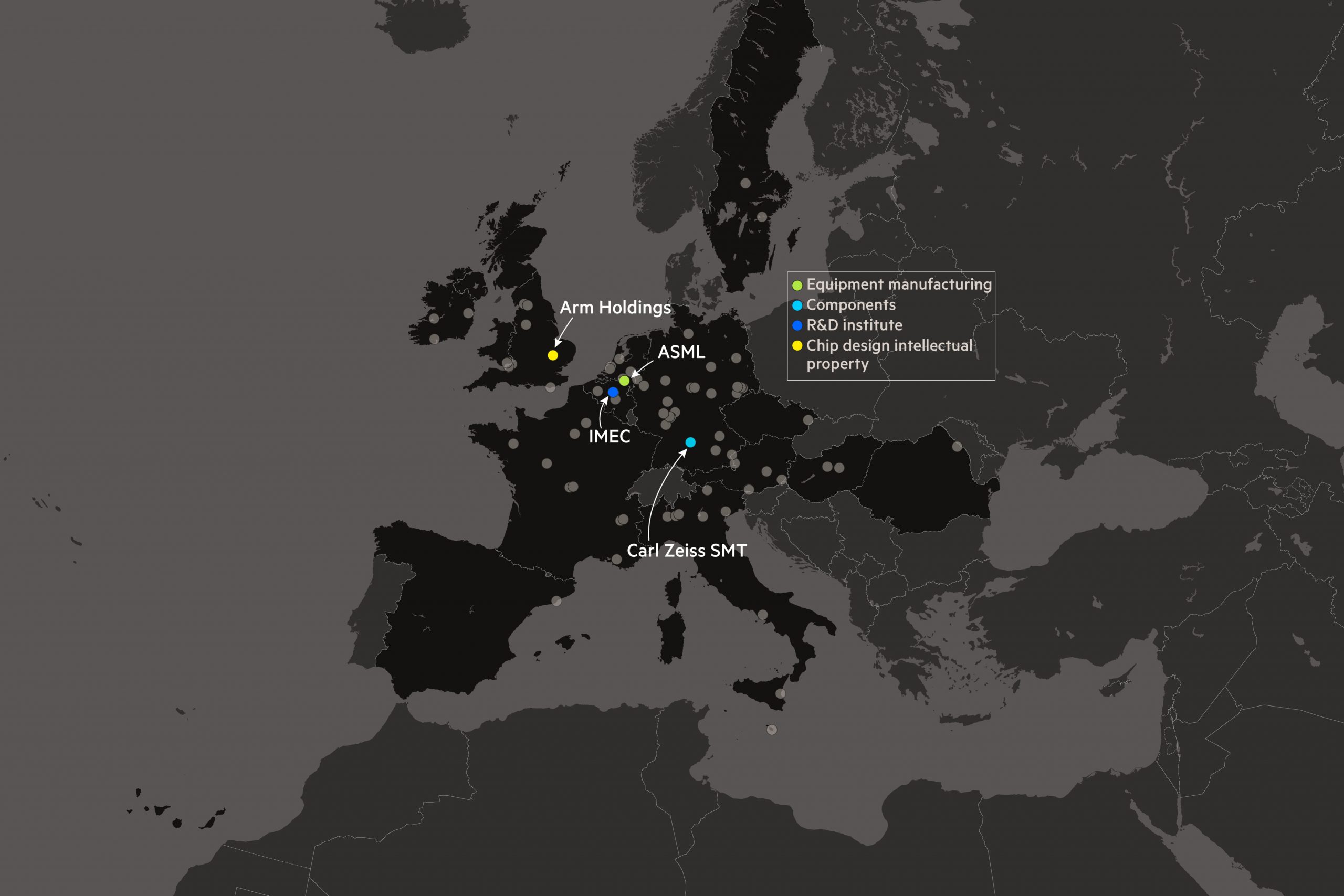

Oberkochen, a small town of just 8,000 people in the south-western state of Baden-Württemberg, is headquarters to Carl Zeiss SMT, the only manufacturer of the mirrors and lenses used in the world’s most advanced chipmaking equipment. Its ultra-precise mirrors and lenses are so accurate that they are capable of a precision 200 times greater than the James Webb Space Telescope.

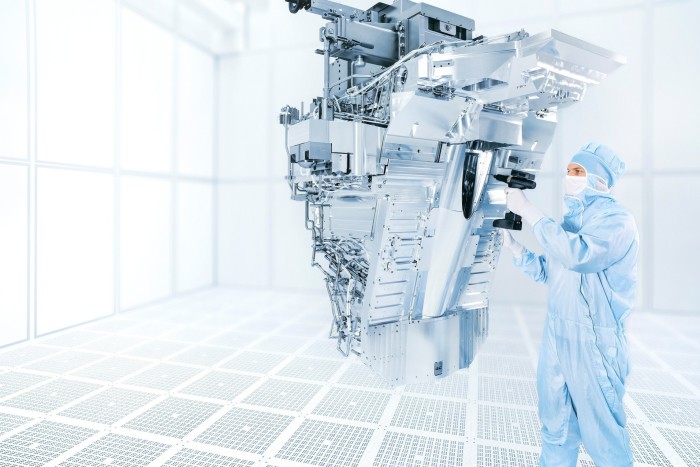

Zeiss has “a unique competence”, says Peter Wennink, chief executive of ASML, the Netherlands-based company that holds a global monopoly on manufacture of the extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) machines required to make cutting edge chips — and is one of its most important customers.

Without Zeiss optics, he says ASML could not make its EUV machines, which use ultraviolet light to scan chip designs on to silicon wafers at a tiny scale. And without ASML machines, it would be impossible to make the most advanced chips needed for future technologies such as artificial intelligence, autonomous driving and quantum computing.

Advanced chipmaking equipment is one of Europe’s hidden strengths as countries around the world try to capture a share of an industry which is at the centre of the modern economy and which is becoming increasingly laced with geopolitical risk.

The semiconductor market exceeded $500bn for the first time in 2021 and is estimated to become a trillion-dollar industry by 2030, according to McKinsey.

Taiwan is the global centre for the most advanced chipmaking. In terms of semiconductors below 10 nanometres — the leading-edge versions of the technology — Taiwan holds more than 90 per cent of global market share.

But growing fears about some form of Chinese military intervention in Taiwan has prompted governments from the US, Japan and many across Europe to rush to incentivise expansion of chip production in their countries, raising concerns that too much capacity will be coming on stream at the same time.

For many countries, semiconductors are a matter of national security as large swaths of the economy increasingly rely on the functionality they provide. Severe shortages during the pandemic have hit production in a wide range of global industries from smartphones and personal computers to servers and automobiles.

Europe is determined not to be left behind as this contest gathers pace.

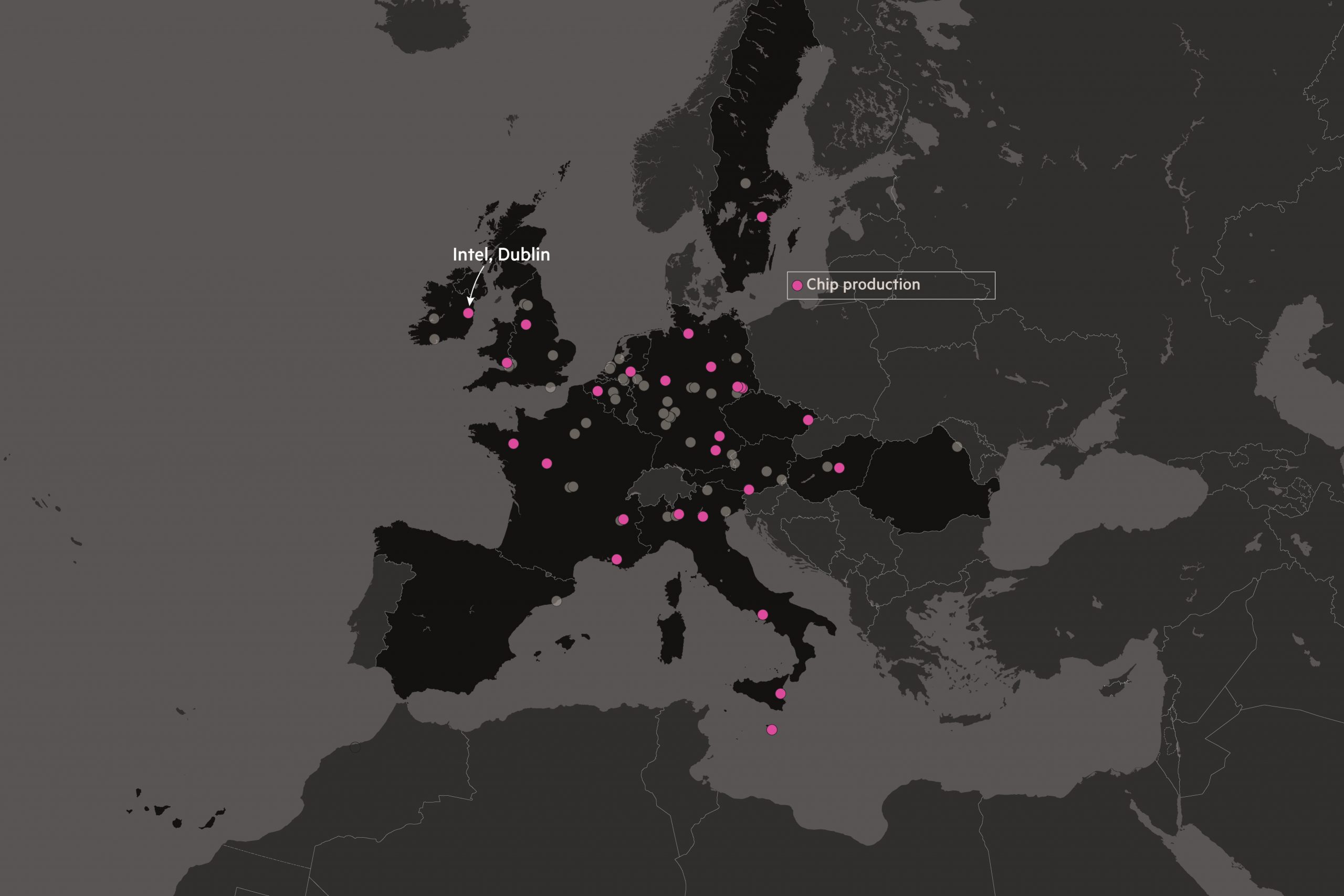

Earlier this year the European Commission unveiled a plan to invest €43bn in an effort to tempt the world’s biggest chipmakers to set up factories in the bloc. Intel, the US chip giant, has pledged an initial investment of €33bn in the bloc, including €17bn for a mega-site in Germany. European chipmakers like STMicroelectronics and Infineon are also expanding their facilities in Europe. The EU is also trying to lure TSMC, the world’s biggest contract chipmaker, to set up large-scale operations in the bloc.

Brussels hopes the investments will double the EU’s share of the global semiconductor market from less than 10 per cent today to 20 per cent by 2030. But more important than market share is to reduce the EU’s dependence on producers in Asia such as TSMC and Samsung at a time when east-west tensions could pose a potential threat to supply.

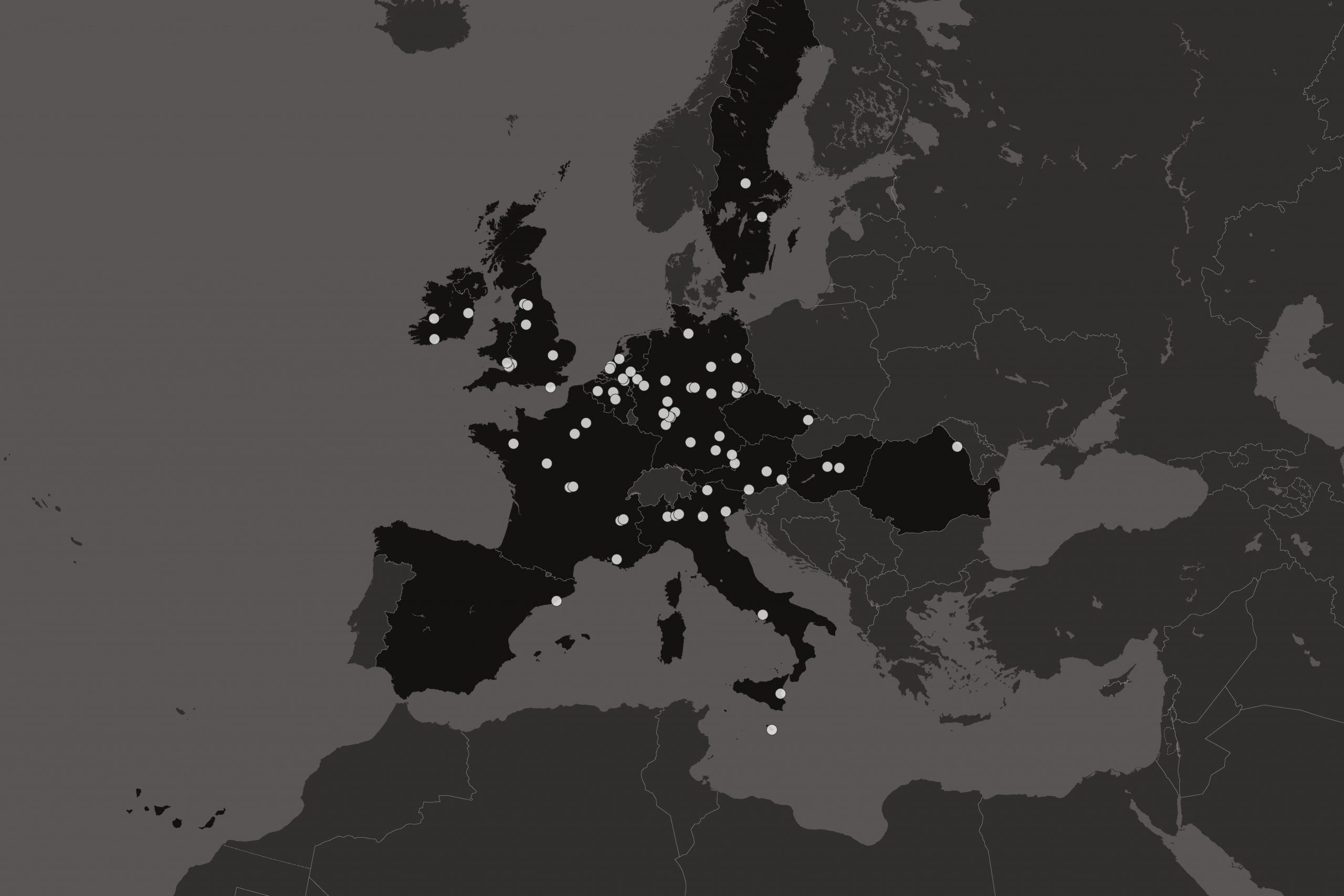

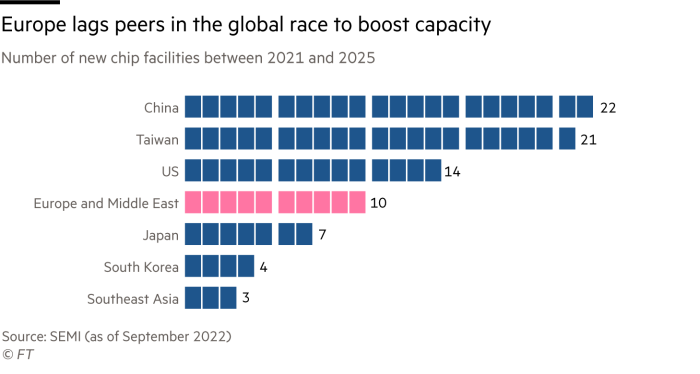

There are at least 81 new chip facilities to be built between 2021 and 2025; 10 will be built in Europe, compared with 14 in the US and 21 in Taiwan, according to the most recent data in September from SEMI, a US-based semiconductor industry organisation.

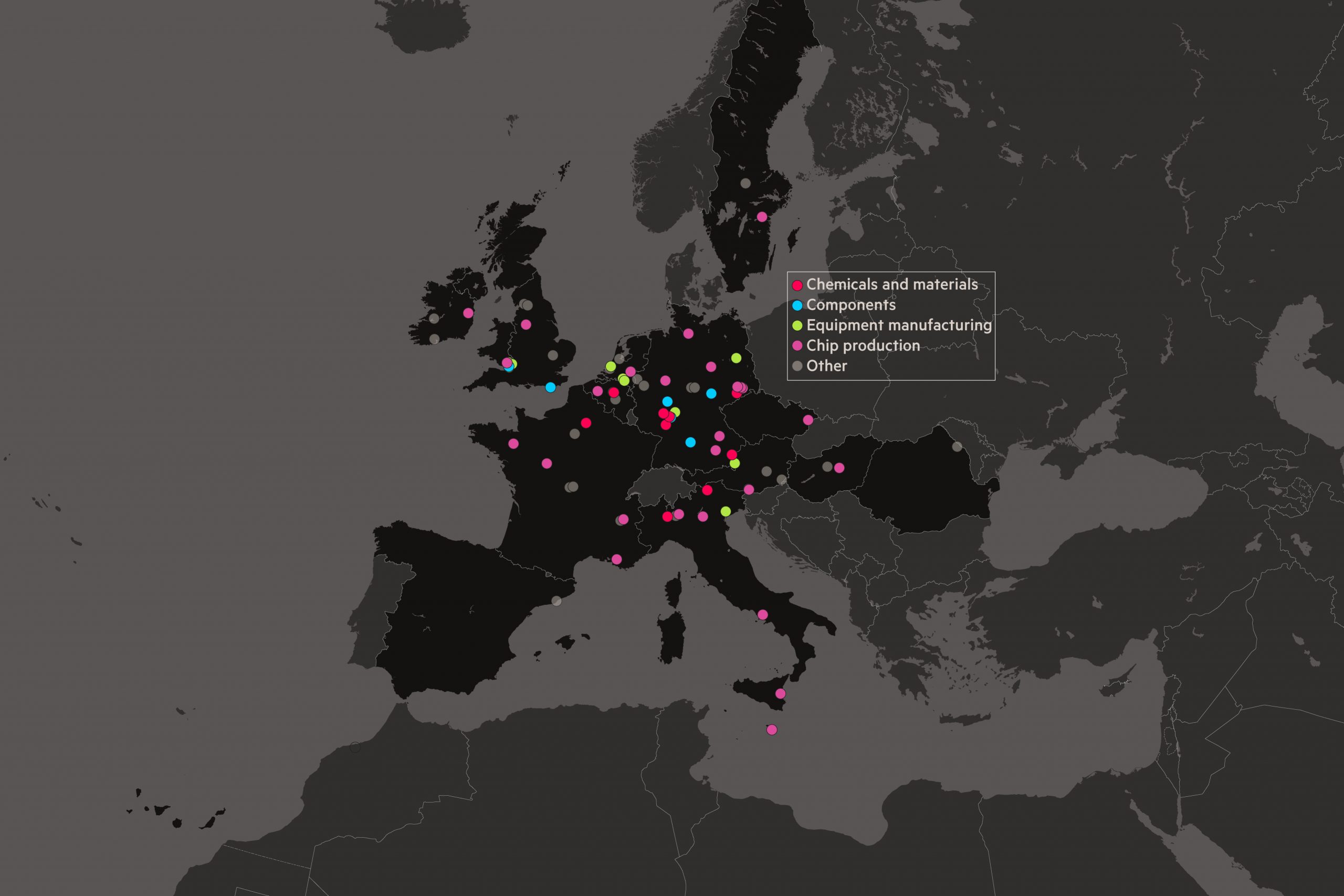

Together with the continent’s solid foundations in chemicals and materials, companies such as Carl Zeiss SMT and ASML and their supply chains will be fundamental to Europe’s ambition to become one of the world’s most important suppliers of the highest-end chips.

But important gaps remain in Europe’s semiconductor push. The amounts of capital required are formidable. And the companies that are looking to supply the chip factories warn that there are not enough skilled workers to keep their plants humming.

“Whether we could reach 20 per cent market share by 2030 is a question mark, but there is increasing pressure because not doing anything will make the situation even worse,” says Lars Reger, chief technology officer at NXP Semiconductor, the Netherlands-based company.

“It’s all about relevancy,” said Wennink at ASML. “You have to stay relevant in the geopolitical context.”

Does it make sense?

Europe’s ambitious plan for microchips, which is built around the European Chips Act, has not been met with universal approval.

Some critics, including industry executives, have suggested that Europe was wasting taxpayers’ money. Far better, they argue, would be to spend the money on expanding capacity of the mature chip technologies that are consumed by Europe’s own industries — such as automotive and industrial applications — rather than face the enormous costs of trying to develop the newest chips. The decline of Europe’s mobile phone industry had left the continent without obvious customers for advanced chips.

As the cost of producing more and more complex chips has escalated, “fewer companies were able to keep up”, says one chip company executive. “Many of those that dropped out of the race were in Europe.”

That has left Europe’s supply chain without some of the key capabilities needed for advanced semiconductor manufacturing.

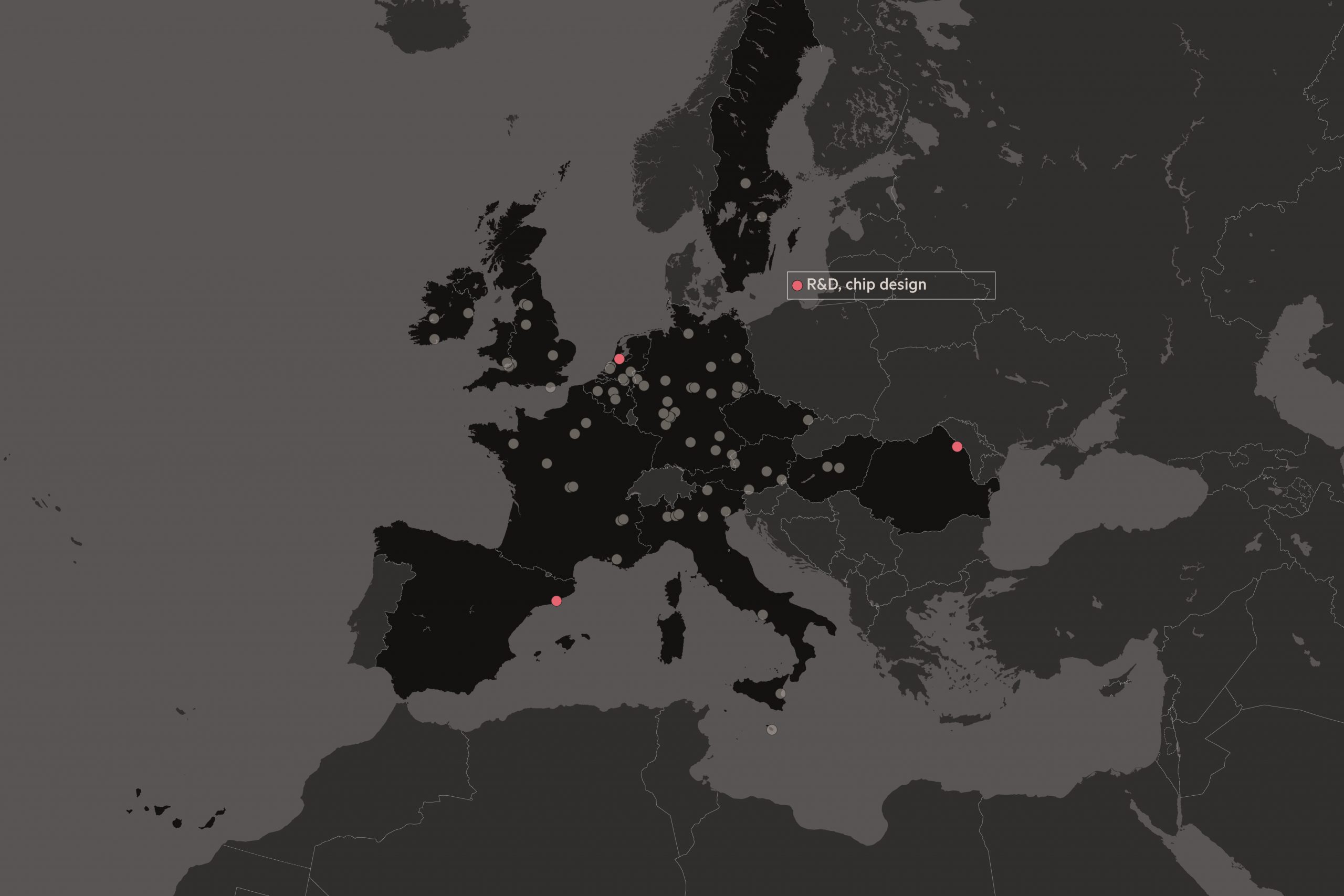

Yang Wang, senior analyst in London with consultancy Counterpoint Research, points out that there are no chip designers in Europe who work in 7 nanometre and below nodes versions of the technology.

“None of the world’s top 10 chip designers are based in Europe while the US leads the world in semiconductor designs,” he says.

The EU does have existing clusters of semiconductor supply chains, such as Leuven in Belgium, Dresden in Germany and Grenoble in France, but Europe will have to ramp up chip design capabilities, and investment into the ecosystem for advanced chipmaking as well as investing in chip manufacturing itself, industry experts say.

Funding is also a crucial factor. The more advanced the chip being made, the more capital-intensive is the process. For example, TSMC’s capital expenditure for 2022 will be $36bn, and this month the company announced plans to triple its investment in Arizona from $12bn to $40bn in the coming years, where it will also bring the more advanced 3nm technology by 2026.

The US this year passed its own Chips and Science Act, a $52.7bn package of incentives and tax breaks.

Building a supply chain as complicated as the one required for the most advanced chip technology will take years to construct — and require even more taxpayer support, say industry executives. Countries such as China, Taiwan and South Korea have invested billions over decades to support their chip manufacturers.

“The European Chips Act is a great tool, because it puts us at the same level of incentives worldwide,” says Jean-Marc Chery, chief executive of STMicroelectronics, a Geneva-based company which supplies chips for the automotive and industrial markets with mainly mature technologies. “But if we have to build [advanced technology] and huge fabs . . . then it’s not very competitive.”

But Europe is not starting from scratch.

The EU’s hold on advanced chip equipment is one important advantage. With EUV machines from ASML, the world’s biggest chipmakers such as TSMC, Samsung and Intel are able to challenge the limits of physics, packing more and more processing transistors on to smaller and smaller chips. Today the most cutting edge in mass production is 3nm — a reference to the size of each transistor on a chip — but technology is taking this to 2nm and below.

“Without EUVs, you would not be able to get to these large densities of transistors in a chip,” says Thomas Stammler, Zeiss chief technology officer. “As we are the only one supplying EUV, we take this also as an obligation to expand and support the chip industry . . . and we are already working on the next generation of EUV.”

Beyond ASML and Zeiss, in which ASML has a 25 per cent stake, Germany’s Trumpf is a world leader in the lasers used by EUV machines. At 220,000C, the plasma created by Trumpf’s lasers — used to generate EUV light — is almost 40 times hotter than the surface of the Sun.

Such advanced technology enables the EUVs to help companies such as Apple squeeze as many as 16bn transistors on the central processing unit of its MacBook today, compared with 1,000 transistors in the electronics devices in the 1970s.

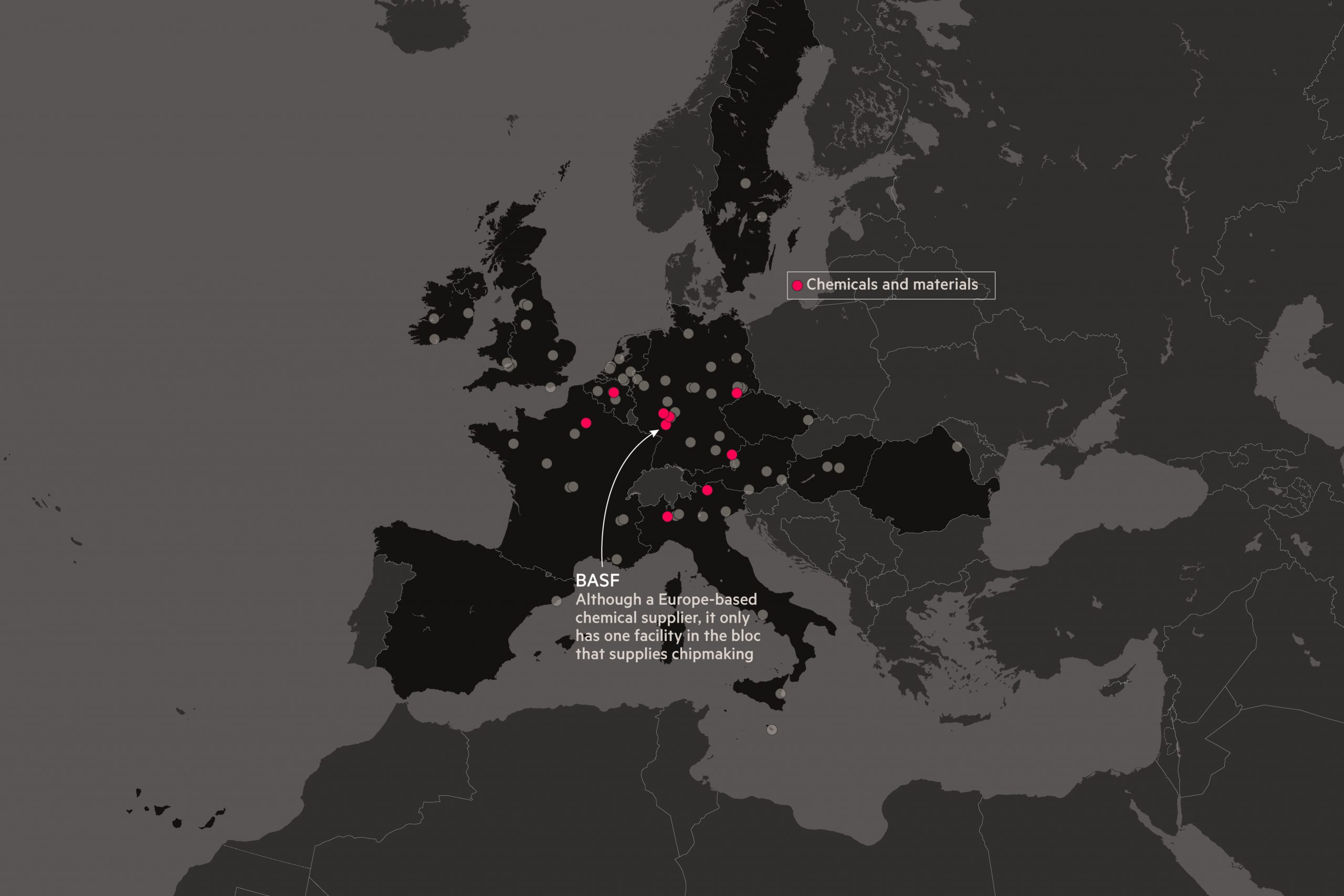

Europe also has a strong advantage in its ability to produce the highly customised, complex materials and chemicals used in advanced chipmaking. These mainly come from a handful of European companies such as Merck, BASF and Solvay, and from Japanese companies such as JSR and Shin-Etsu Chemical.

It also has one of the world’s foremost research hubs in IMEC, the nanotechnology research centre outside Brussels that is used by the most advanced chipmakers to build prototypes. Other world-renowned research centres include Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes and France’s CEA-Leti.

But there are still challenges. Other countries are investing far more than those in Europe to build up their own chipmaking capabilities, and ecosystems are already starting to develop around new plants.

In Europe critical chemical and material suppliers have been slower to invest than those in the US and Taiwan. Some in the industry suggest this is because the European Chips Act does not sufficiently cover investment beyond chipmaking, or because European environmental regulations make expanding chemical facilities more difficult. And of course, Europe’s gas crisis has driven up already high energy prices, forcing the bloc’s energy-intensive chemicals industry to shut or suspend production of some products. Expanding in Europe right now is not attractive without strong incentives, say industry executives.

“Supply of chemicals to the new semiconductor fabs require investments in dedicated assets. Therefore, a lack of state support would definitely be a hurdle for suppliers of chemicals,” Solvay president Rodrigo Elizondo tells the Financial Times. “In our view, the absence of a robust regional supply of chemicals will definitely jeopardise the operations of European semiconductor fabs.”

BASF and Solvay expect chemical and material shortages in the coming years when the new chip capacities ramp up, unless investments are made in these areas.

“Everyone talks about semiconductor manufacturing, but not enough attention is given to the chemicals needed to produce these microchips,” says Lothar Laupichler, BASF’s electronic materials senior vice-president. “It almost feels like chemicals are looked at like water or electricity, you open the faucet and it comes right out, but this is a misconception.”

Kai Beckmann, member of the executive board of Merck and chief executive of its electronics division, adds: “We need to look into this jointly with the European Union, because we are talking about very highly specialised material that may not be well captured in the European ambitions.”

Finding the staff

Europe faces one even more basic problem: finding enough skilled workers. A survey by the European Labour Authority of the biggest labour shortages in the EU found that engineers and technicians — the pillars of the chip industry — were among the top four talent shortfalls in 10 countries.

Companies such as Germany’s Infineon, Edwards Vacuum in the UK, which is the crucial component and subsystem provider to ASML, and AT&S in Austria, one of the leading suppliers of the high-end chip substrates on which semiconductors are mounted, have all warned that foreign talent will be crucial to the further development and sustainability of Europe’s semiconductor industry.

Andreas Gerstenmayer, AT&S chief executive, says his company is struggling to find the 800 skilled workers it needs for its new research and development centre in Austria. “We have to reach out globally to hire talent, because the experience and the technology [of chip substrates] are not yet available here.”

Martin Stöckl, Infineon’s human resources boss, says the whole supply chain will be chasing the same talent, making matters worse. “The talent shortage issue is serious in Europe,” he says. “If you do a quick calculation, we [Infineon] will build a new fab, STMicroelectronics and Intel are expanding too. We [companies] will need at least thousands more engineers and technicians in the coming years.”

Yet the battle is far from lost, say industry executives.

Despite all the challenges, industry executives are upbeat about Europe’s prospects in this critical industry. Having companies such as ASML, Zeiss and Trumpf is not a bad place to start.

“Europe did retain real strength over the years in semiconductor manufacturing equipment,” says a senior Intel executive. “That has really given it a chance to re-enter the market that otherwise it would not have had. Without those beachheads, it would have been very, very difficult for Europe to come back.”

Additional reporting by Peggy Hollinger and Joe Miller

Cartography and data visualisation by Liz Faunce and Alan Smith