Length selection produces single-chirality nanotubes

Theoretical physicists at Rice University in the US have proposed a practical new approach to growing carbon nanotubes with a single chosen “handedness”, or chirality. If realized experimentally, the approach would fulfil a long sought-after goal in nanotechnology and could make nanotube-based technologies more accessible.

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are rolled-up hexagonal lattices of carbon just one atom thick. Thanks to their excellent electrical and mechanical properties, they show promise for many applications, including ultra-strong fibres and conductive wires. They can be single-walled or multi-walled, and the way the hexagons are angled within the lattices – their chirality – determines whether they are metallic or semiconducting.

Nanotubes normally grow in a way that produces single and multiple walls and different chiralities at random. However, some applications (like highly conductive fibres or the semiconductor channels of transistors) require batches with just one type of chirality. Separation techniques such as centrifuging can meet this need, but they are complex and costly.

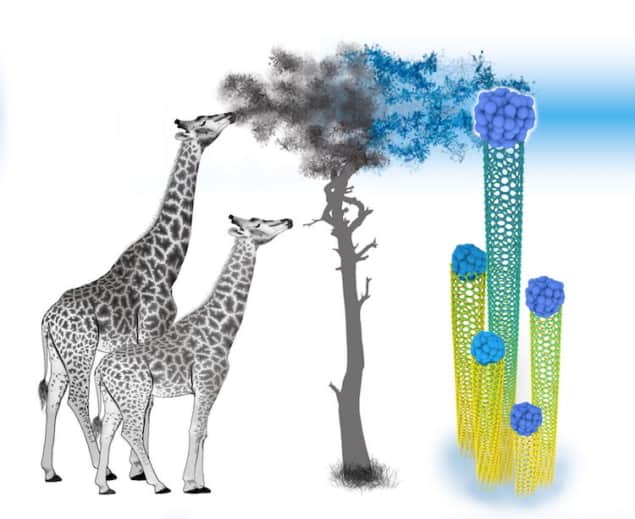

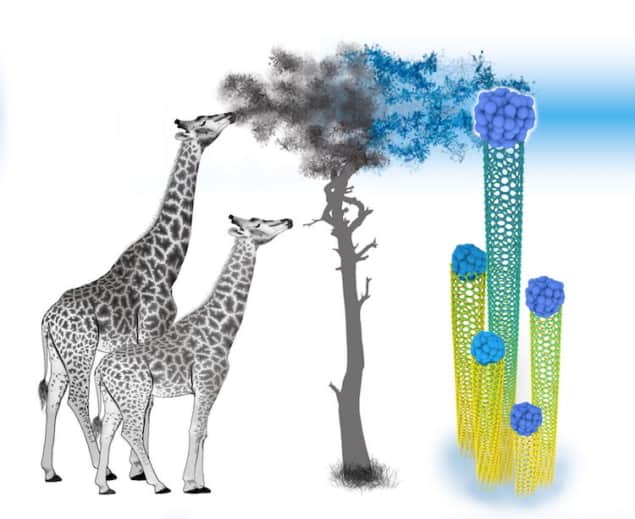

Growing like Lamarck’s giraffes

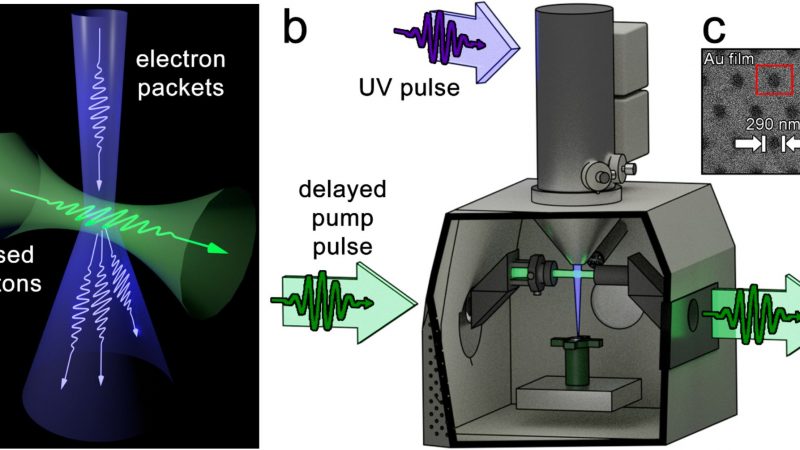

The new approach developed by Boris Yakobson and Ksenia Bets at Rice requires would-be chiral nanotube growers to set up an optimized localized zone in the CNT growth chamber. This zone contains a precursor feedstock from which the CNTs are created, and Yakobson and Bets’ “recipe” calls for it to move along the reactor at a prescribed speed, allowing only some types of CNT to be “fed”. Since tubes with different chiralities grow at different speeds, they can then be separated by length, leaving the slower-growing types behind.

The researchers describe their method with an analogy to “Lamarck’s giraffes” – a 19th-century theory suggesting that giraffes evolved long necks due to a gradual evolutionary selection of animals that can reach progressively higher for tree leaves to eat.

“It works as a metaphor because you move your ‘leaves’ away, the tubes that can reach them continue growing fast and those that cannot just die out,” says Bets. “Eventually all the nanotubes that are just a tiny bit slow will ‘die’.”

As the main obstacle to widespread industrial use of nanotubes, an in-growth method of chirality selection was a highly-coveted goal for researchers in this field, says Yakobson. “Our new technique can unlock many CNT-based technologies developed over the last decades for mass production,” he claims. “Indeed, chirality selection means single, well-defined electronic bandgaps for transistor or well-defined optical properties perhaps for solar cells applications.”

Chirality affects current flow in graphene transistors

The Rice team, who detail their study in Science Advances, hope their technique will now be realized in a real-world experiment. “Now that the paper has been published, experimental groups worldwide can try implementing this methodology on their particular growth setups, exploring the possibilities and limitations of the approach pushing the technology development even further,” Yakobson tells Physics World.