The Future Technology of the Year 2100

In the year 1900, the world was in the midst of a machine revolution. As electrical power became more ubiquitous, tasks once done by hand were now completed quickly and efficiently by machine. Sewing machines replaced needle and thread. Tractors replaced hoes. Typewriters replaced pens. Automobiles replaced horse-drawn carriages.

A hundred years later, in the year 2000, machines were again pushing the boundaries of what was possible. Humans could now work in space, thanks to the International Space Station. We were finding out the composition of life thanks to the DNA sequencer. Computers and the world wide web changed the way we learn, read, communicate, or start political revolutions.

So what will be the game-changing machines in the year 2100? How will they make our lives better, cleaner, safer, more efficient, and more exciting?

We asked over three dozen experts, scientists, engineers, futurists, and organizations in five different disciplines, including climate change, military, infrastructure, transportation, and space exploration, about how the future technology of 2100 will change humanity. The answers we got back were thought-provoking, hopeful and, at times, apocalyptic.

Climate: Adapt Until We Change

In 2023, our planet is in trouble. Two centuries of fossil fuels have led to multiple environmental concerns that we are only now beginning to understand. By 2100, the world’s sea level is predicted to rise anywhere between one foot to 12 feet, putting billions of people at risk. Despite these dire warnings and well-founded fears, humans have always had a knack for adaptation.

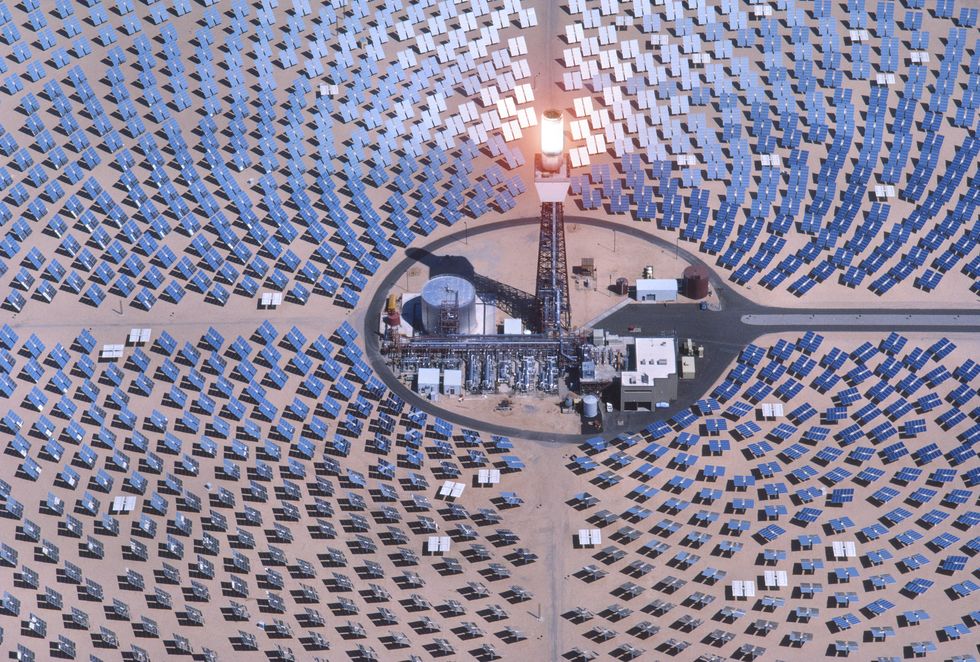

First is solving the biggest problem—pollution. If fossil fuels are no longer around, then what will be powering our world in 2100? Hydro, electric, and wind are all obvious choices, but solar and fusion tech may prove the most promising.

The classic joke about fusion energy is that widespread adoption is always just “20 years away” but private and government-funded projects are in mad pursuit of this carbon-free energy source that would effectively create the “perfect battery.”

But if fusion remains out of reach, we’ve always got the Sun. Although solar is already an important cog in any modern energy grid, in the year 2100, solar could play a much more central role. John Mankins, former chief technologist for NASA Human Exploration & Development of Space, explained that it will be “solar power satellites with long-range wireless power, delivering vast amounts of affordable solar energy to global markets” that will be cleanly powering our planet decades from now.

But capturing the Sun’s rays is only the first step, we still need to figure out a way to store it. By 2100, says disaster resilience expert and managing director at Deloitte Josh Sawislak, we very well could have solved this problem by making everything a solar power collector, from the paint on our house to the asphalt on the road. People will then store this energy in a small, portable solar power device about the size of a modern-day smartphone.

“I’ll have a small device that I could run my car on,” says Sawislak.

The Sun’s energy will be so useful to the future humans, that carbon power will disappear—almost. “Carbon-based power by 2100 will be like gas-lighting today,” says Sawislak. “You are going to see it… just in places that are trying to be historic.”

While the large-scale manipulation of the atmosphere and environment remains controversial, many scientists think that it’s worth exploring if we want any hope of keeping Earth human-friendly. Although the idea of massive machines extracting pollution and pumping life-saving mixtures sounds great, that vision comes saddled with a lot of caveats.

The big concern is catastrophic consequences by manipulating our atmosphere. In 2007, Harvard researchers concluded that geoengineering was just too risky right now—but what about in the 22nd century? What would such future technology look like?

Maybe they’ll be fleets of large drones blanketing the upper atmosphere and emitting tons of extremely fine dust-like material into the sky above us? Or maybe it will be machines “that can efficiently remove greenhouse gases not only from point-sources, but also from the atmosphere on a large enough scale to halt and reverse global climate change,” says Lisa Alvarez-Cohen, professor of environmental engineering at Berkeley.

But we don’t have to wait for a new century for this kind of tech. In fact, it’s already in the works.

War: The Rise of the Robo-Soldier

As long as Homo sapiens has walked the Earth, war has been an unavoidable part of life, and there’s no doubt that wars will still be around decades from now. But in the next century, war may look a lot different than it does today. By 2100, human fatalities could decrease because of the increased reliance on artificial intelligence, automation, and more exact weaponry.

Merging machines, artificial intelligence, and humans on the battlefield in the 22nd century is hard for our 2023 minds to understand. These human/machine mind melds may seem like science-fiction, but DARPA told Popular Mechanics that war could soon use “an unprecedented degree of human-machine symbiosis… with interfaces between these powerful systems and their human operators as seamless as possible.”

“Weapons will be smaller, faster, more versatile, and less lethal,” Gil Metzger, the director of applied research at Lockheed Martin, told Popular Mechanics. “They will be able to complete the mission with higher probability of success, but with substantially less collateral damage and fewer casualties.”

But not everyone believes that military AI and automation is a good thing. Mankins thinks it’s dangerous imagining a 22nd century where machines are “sanctioned by (world) governments with authority and ability to compel individual human compliance with force.” Like a future dominated by Gort or Skynet.

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Not only will soldiers change in the new century, weapons will also be almost unrecognizable. Iain McKinnie, chief technologist at Raytheon Intelligence & Space, says that laser and direct energy equipment are future weapons of choice because of their accuracy, “low cost per shot,” and a nearly limitless magazine—all in a smaller package than an AK-47.

McKinnie says if we get closer to using a 50kW generator to power a 50kW laser beam, it’s not inconceivable that in 2100 we will have “handheld laser weapons.” In other words, set phasers to kill.

In November 2017, the Air Force Research Lab awarded a contract to Lockheed Martin for the “design, development and production of a high power fiber laser” with plans to test it on a tactical fighter jet by 2021.

Infrastructure: Faster, More Efficient, and Underground

Despite our country’s infrastructure constantly receiving poor grades, there’s optimism that by 2100 many of these problems could be fixed with help from machines both big and small—like really small.

Imagine thousands, or even millions, of tiny machines working together in a “swarm” to repair a bridge quickly and precisely or constructing emergency infrastructure during massive floods. That’s the future potential of nanotechnology.

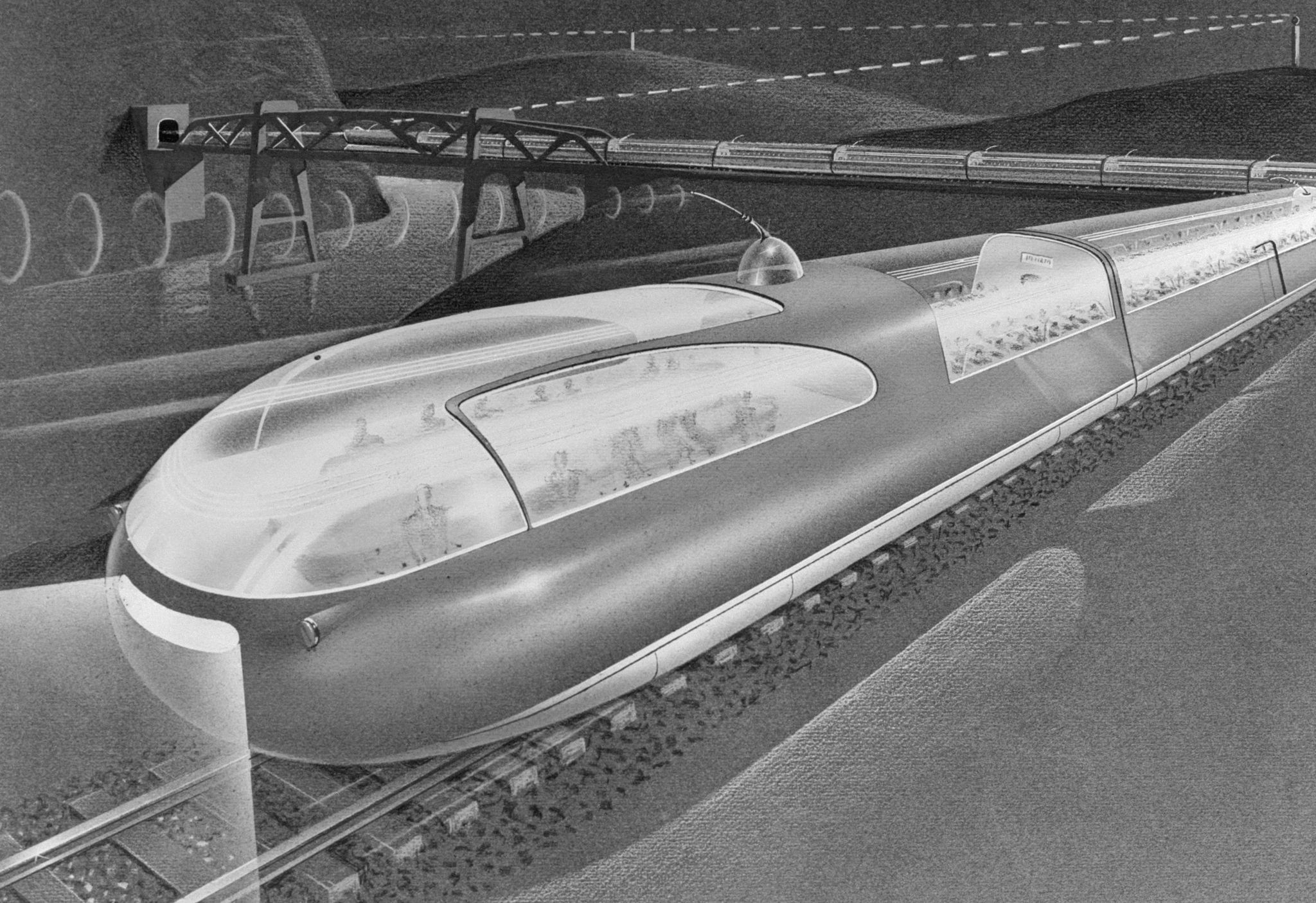

But while these little machines work for repairs, eventually an outdated transit system needs replacing. By 2100, all-new, high-speed railway systems—or even hyperloops—will have replaced the current and outdated one. Systems that are in the first phase of production, like the one from L.A. to San Francisco, are just the beginning. By the end of the century, railroads and tunnels will be crisscrossing the country with high-speed transportation zipping along a maintained, privately-funded system of infrastructure.

By 2100, it’s probable you’ll be able to go from D.C. to New York in less than 30 minutes.

Although lots of this future tech help solve big problems, being able to fully tap into the resources locked in our oceans might have the most widespread impact. Despite 71 percent of the Earth’s surface being covered in water, clean drinking water is still a massive problem. Over 96 percent of the planet’s water is undrinkable due to it being saline or otherwise contaminated.

But Berkeley’s Alvarez-Cohen thinks the next century will have it figured out, having developed a machine that filters water at max efficiency, perhaps ending the global water crisis.

With one major necessity solved, another human need also needs fixing—housing. By most estimates, the Earth will be host to 11 billion humans by 2100, leaving little space for such for humans to live and thrive. But under our feet, there’s still plenty of space, and large boring machines tunneling under major metropolises will make infrastructure build-out underground relatively fast and cost-effective.

Building underground, according to Infrastructure Week’s Zach Schafer, will help solve our current infrastructure crisis and open up more space for humans to live in the future. “Underground systems are reliable and more protected from the elements,” says Schafer. “[We] can leave our lives on the surface free from the noise and divisions caused by overpasses and highways that cleave neighborhoods in two.”

Transportation: By Land or By Rocket

Although people always clamor for a future with flying cars,

“Creating future autonomous aircraft is actually much easier than doing autonomous cars because there is less of a worry of running into anything in the sky,” says Stephen Pope, former editor-in-chief of Flying Magazine. “Eventually we’ll get to the point where pilots aren’t needed at all.”

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The federal government also believes in such a future. The former U.S. secretary of transportation Elaine Chao wrote to Popular Mechanics that, in 2100, she foresees drone aero taxis sharing the skies with piloted aircraft. This will speed up air travel so much that, says Chao, we will be able to “travel across the globe in a fraction of the current time… it is entirely possible that people could be commuting to and from work in other countries on a rocket, connecting Americans to global opportunities.”

This kind of intercity rocket travel is another dream also shared by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which in 2017 announced a plan to create a system that can get you anywhere in the world in less than an hour.

But most humans will reap benefits from transportation plans that are slightly more grounded. Autonomous cars and trucks will lead to less traffic, less accidents, and less infrastructure, for example.

But autonomy won’t just reshape how humans move, but also how things move. In 2023, millions of goods are transported along our nation’s roads. Jaimee Lederman, a transportation planning researcher at UCLA, predicts that in 80 years a large portion of our goods will be delivered by drones or by pneumatic tubes.

It’s even possible that shipping itself will become a relic if 3D printing technology embraces its Star Trek replica ideal. These machines could feasibly make everything from your next pair of shoes to your next mushroom pizza.

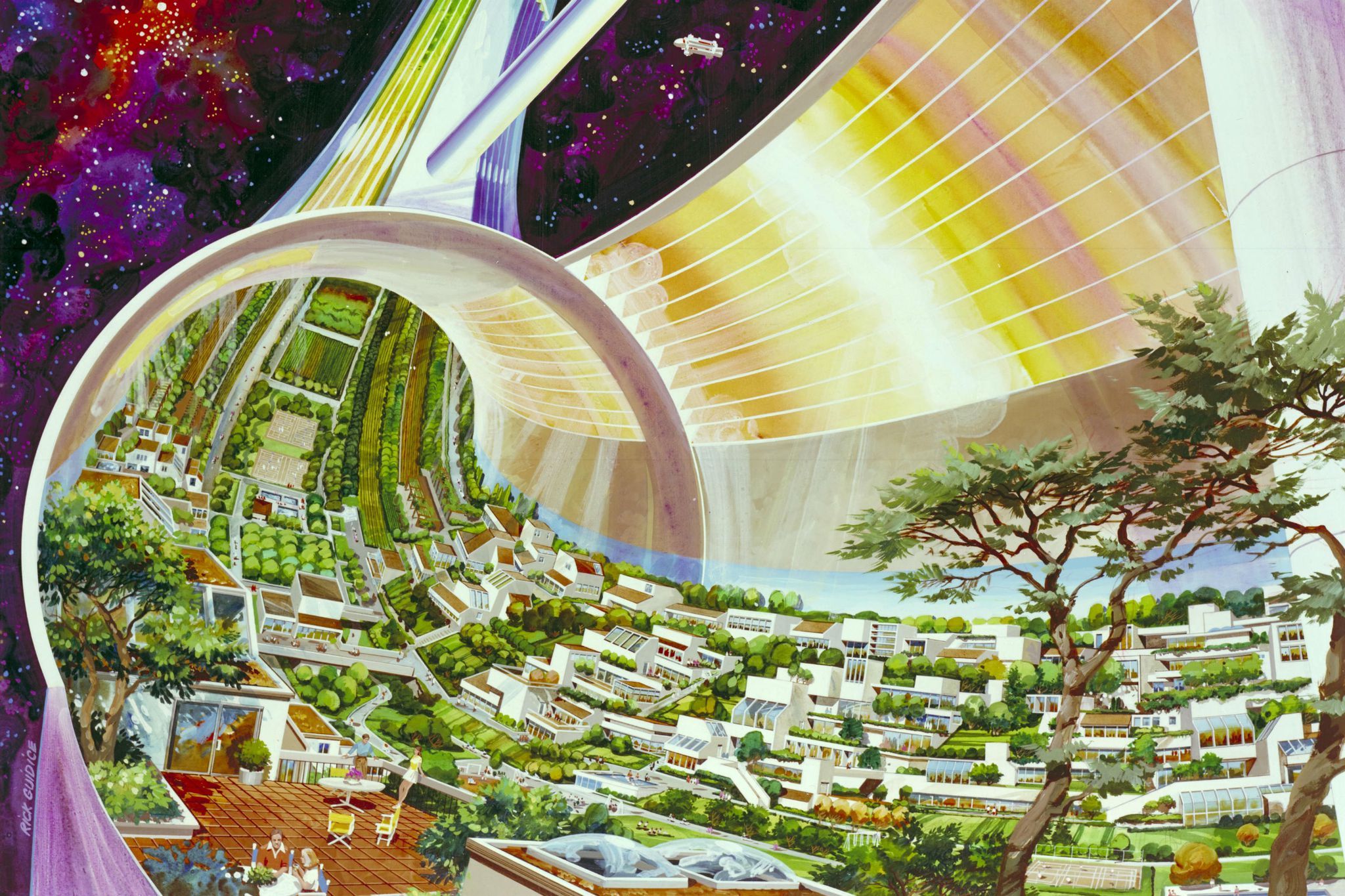

Space: Humanity’s New Home

Today, working and living in space is limited to a privileged few. But by 2100, it will be an everyday routine.

Fantasized about since at least the late 19th century, elevators to space are rather simple in concept, but tough in practice. The basic idea is that a car is tethered to a immensely strong line (perhaps made of carbon nanotubes) by either powerful magnets or robotics that allows it to climb thousands of miles into space. These elevators would make space travel cheaper, easier, and more regular.

While there are projects in the very beginning stages, the main problem is that there isn’t a tether material strong enough, light enough, and cheap enough. However, these problems will likely be solved by 2100, and space elevators will give a larger swath of the population a chance to rise above Earth.

“It’s about bringing down the cost to space access,” says Kelvin Long, co-founder of the Initiative for Interstellar Studies, “It opens up the possibility for establishing an independent, solar system-wide economy independent of Earth… through space hotels, missions to the moon, Mars, and beyond.”

These elevators won’t be reserved just for space tourism, they’ll be used for daily commutes. By 2100, there will be self-sufficient colonies on the moon, and more ambitiously, Mars. While they still may be small in number—likely only a few hundred people—they will require machines that can mine available resources and repair themselves.

Asteroid mining, something that NASA is already preparing for with the

While space elevators will help supply Mars colonies and mine asteroids, advancements in propulsion will allow us to explore deeper into the galaxy like never before. Nuclear technology and powerful directed laser beams will lead the way in significantly reducing travel time to the furthest reaches of the Milky Way.

The NASA Authorization Act of 2017, sponsored by Senator Ted Cruz and signed into law by the President, reads that “advancing propulsion technology would improve the efficiency of trips to Mars… reduce astronaut health risks, and reduce radiation exposure, consumables, and mass of materials required for the journey.”

Ron Litchford, NASA’s principal technologist for propulsion, told Popular Mechanics that this is the first stepping stone: “It appears the U.S. is poised to shift to a space policy goal of achieving human exploration of the solar system by 2100.”

Litchford explained that it will be a combination of a compact nuclear space power system and “very large, high-power laser arrays for power beaming across the solar system” that will get us further out into the cosmos much quicker. He estimates that in the next century we will be able to travel up to 10 to 20 percent the speed of light, or about three times faster than the Parker Solar Probe launched in 2018.

Extrapolate even further and these new propulsion technologies could lead us to establishing a human colony on Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Meanwhile, unmanned small space probes—the 22nd century descendants of Voyager and New Horizons—will travel even deeper into our universe, reaching as far as Alpha Centauri.

Andreas Hein, executive director for the Initiative for Interstellar Studies, says that these probes will likely be smaller than a credit card powered by a nuclear battery the size of a quarter. The camera will only be slightly larger than the one we now have on our iPhones, yet will send back high-res “close-up images of an exoplanet with vegetation.”

By 2100, machines might help us answer humanity’s greatest question: Are we alone?

Matt is a history, science, and travel writer who is always searching for the mysterious and hidden. He’s written for Smithsonian Magazine, Washingtonian, Atlas Obscura, and Arlington Magazine. He calls Washington D.C. home and probably tells way too many cat jokes.