Resilience and representation in research: In conversation with Sreeja Narayanan

Indian science is shaped as much by its systems as by its discoveries. In this landscape, resilience is rarely dramatic — it is built through steady choices, adaptation, and persistence. Sreeja Narayanan’s journey reflects this quiet strength, as she builds an interdisciplinary research career in India while mentoring students and navigating institutional and personal transitions.

Indian science is shaped not only by our laboratories and publications, but also by the systems that enable (or constrain) those who work within them. Today, early-career researchers navigate dynamic funding landscapes, evolving institutional expectations, and personal life transitions, all at once! In this context, resilience rarely presents as a dramatic turning point. Instead, it is built through consistent and intelligent choices like choosing to stay, questioning established paths, and building careers where structures do not yet fully exist.

Sreeja’s career is a reflection of this quiet, sustained form of resilience. Trained as a nanomedical scientist, she has spent over a decade working at the intersection of engineering and biology, developing approaches that connect nanotechnology with immunology and translational medicine. Her journey is as much about building research systems and mentoring young scientists in India as it is about scientific outputs themselves.

From nanotechnology to translational Science

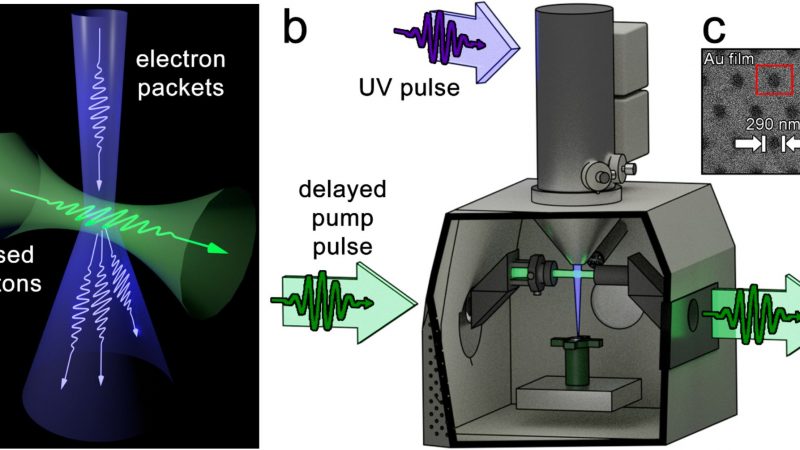

In 2015, Sreeja completed an integrated MTech – PhD in Nanomedical Science from Deepthy Menon’s group at Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Kochi. Her doctoral research focused on adjunct strategies to manage chemotherapy-induced inflammation in cancer patients. Working within a hospital environment exposed her early to clinical realities. Interactions with patients and clinicians helped her take the pulse of the system, and identify areas where research interventions could help.

“It was a valuable experience”, she reflects. This early exposure shaped her long-term interest in translational, impact-oriented science. Rather than remaining within a single disciplinary silo, she wanted her research trajectory to integrate nanotechnology, immunology, microbiology, and materials science.

After her PhD, Sreeja received the UGC D.S. Kothari Postdoctoral Fellowship in 2016, which she used to expand her research into infectious diseases. Joining Sarita Bhat’s laboratory at the Cochin University of Science and Technology (CUSAT), Sreeja worked on microbial exometabolite-based nanoparticle systems for inflammation management, calling this a foundational experience, setting the stage for her current work on immunomodulatory therapeutics.

Two years later, she was awarded the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Early Career Fellowship, enabling her to consolidate an interdisciplinary research programme and begin establishing an independent scientific identity within CUSAT.

Building a lab without a formal title

At the time, Sreeja did not hold a permanent faculty position. Her early career fellowship coincided with the COVID-19 lockdown, a period marked by uncertainty.

“While that was a challenging period, the fellowship gave me significant independence within the department. The institute allowed me to present my five-year research plan and explain how I intended to carry out my project during such uncertain times”, Sreeja says. With the support of her mentor, Sarita, she approached the university to explore the possibility of supervising PhD students.

After months of discussion, she was formally recognised as a PhD guide under the Faculty of Sciences in early 2021.

This would not have been possible without the India Alliance grant. It gave me the confidence and independence to approach the institution, secure space, and take on greater responsibility — not just as an Early Career Fellow, but as a research guide capable of running a PhD programme. It was a major leap for me”,

Sreeja shares.

During the lockdown, she inducted two women students into her immunotherapy-focused programme. Both are now close to completing their doctoral work.

Negotiating institutional complexities

Within her department, Sreeja found mentors who treated her on par with assistant professors, encouraging her to teach postgraduate courses in immunology and nanotechnology, recruit PhD students, and participate in administrative work. She especially mentions the role of her mentor – Sarita – who ensured that her growth was not confined to the lab. Sarita pushed her to establish her own independent space and work within CUSAT.

Yet the absence of a permanent position also meant navigating bureaucratic hurdles.

Processes like approvals and signatures required multiple layers of verification. Often, I was told that this was necessary because the institution could not hold me accountable in the same way as permanent staff”,

Sreeja shares, as she reflects on those initial days as quite frustrating.

Rather than withdrawing, she chose to engage more deeply with administrative systems, learning procedures, handling accounts, and preparing indents. “At times, it meant putting everything else aside and starting from ground zero. While challenging, this process helped build rapport over time, and the administration gradually became more supportive”, she shares.

The role of mentorship across career stages

Sreeja’s trajectory has been shaped by mentors at different points in her career. Her PhD supervisor Deepthy Menon, a biomaterials scientist at Amrita Center for Nanosciences and Molecular Medicine, Kochi, introduced her to nanotechnology as an interdisciplinary field and welcomed all her questions and encouraged her to learn from mistakes. This mentorship helped Sreeja develop problem-solving skills and confidence in navigating research challenges.

“Later, when I joined Sarita’s lab, I was very intentional about the areas I wanted to explore. She helped me bridge disciplines and taught me early lessons in leadership. She trusted me with mentoring students and encouraged me to take responsibility, eventually pushing me to apply for research guideship”, shares Sreeja, reflecting on this period as truly one of the most pivotal moments in her career.

During the early phase of her postdoctoral career, Sreeja came in contact with Praveen Vemula from BRIC – inStem. Praveen has since influenced her thinking on translational research and societal impact. Observing how he embodies that purpose-driven approach to science, while nurturing motivation and aligning research with societal impact, has deeply influenced Sreeja’s own approach to her research.

This layered mentorship, she believes, is critical for early-career researchers navigating complex academic systems.

Discovering a scientific identity while negotiating personal life choices

Sreeja did not always imagine a career in science. As a student, science was simply another subject until she began to see how it translated into everyday technologies like the internet and medical advances. In her early twenties, Sreeja’s interest in science truly crystallized, and supported by timely opportunities, she was ready to embark on her academic journey.

Alongside her academic journey, Sreeja’s life has been shaped by significant personal decisions. Sreeja met her partner during their PhDs. While her partner’s career took him to the US and Europe, she remained in India, navigating her doctoral training alongside motherhood to two children.

“The conventional suggestion was to move abroad on a family visa, and eventually find opportunities overseas”, Sreeja recalls. Instead, she chose to stay back, supported by her father, to build both her family and career in India.

We were a young family, and I didn’t want to feel burnt out or overwhelmed away from home.I didn’t want to be in such a situation where I lost confidence and felt low about myself. I’ve come a long way already! So I consciously decided that I would stay back in India so that my children and I could get the care and emotional strength necessary for growing years and not feel displaced in a foreign land.”

While her decision to stay back in India was an informed choice, she says that postdocs from India seeking a faculty position in the country are often asked, “Why not a postdoc abroad?”, Sreeja questions the relevance of this expectation in an era of digital collaboration. “International mobility is no longer limited to physical relocation”, she says.

Sreeja agrees that making these choices did not come easily, but she is aware that it came from a place of confidence and decisiveness. She says, “You have to identify where your base is, where your support is. Take decisions that are authentic to your situations. You have a long life to live. The world has come a long way so let’s not follow trends that are already outdated”.

After his career in the US and Europe, Sreeja’s partner eventually moved back to India and established himself as a faculty member, joining Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Kochi. Today, their daughters are thriving teenagers, reflecting the stability and balance the family worked hard to build. Sreeja adds, “Now, I happily look back that my decision had the power to change the decisions of an entire family. “

The power of women’s collectives in supporting the next generation

Sreeja has seen similar negotiations among her students, including those balancing doctoral work with family responsibilities. These experiences inform her commitment to mentoring young women scientists.

I want the girls, both at home and in the lab, to not sit back and feel they cannot do anything. Let’s bring out our own dreams. And India needs a lot of innovation in thought as well.”

She also reflects on the role of women’s collectives such as POWER Bio. While policies like “Beti Bachao Beti Padhao” in India encourage girls’ education, she argues that leadership and sustained career growth must also be supported. She believes progress must be holistic, where women are supported to make their own choices — whether that involves building families, pursuing careers, or taking on leadership roles. “Equity has to percolate into all spheres of life.”

Collectives, such as POWER Bio, Sreeja believes, facilitate support, sharing and exchanging stories and opportunities, sisterhood and most importantly, mentorship. Other than offering a common platform to learn to navigate academia from highly accomplished fellow women scientists, Sreeja adds that what she finds most valuable in POWERBio is its role in “supporting women through life transitions like, motherhood, caregiving, etc., I see friends and members like Radhika, Vineeta, Suhita and many more build an overall supportive environment. They lend their ears, give us strength, and also remind us that as women we’re not alone, we have that empathy.”

She adds that this shared empathy and understanding will go a long way in ensuring that women will no longer need to compromise their professional journeys for ‘biological timing’, and vice versa. “A visionary country like India needs young people, bolder women, which institutions like POWERBio can help develop”, Sreeja adds.

In tracing Sreeja’s journey, it becomes clear that resilience in research is not a singular act, but a continuous practice of adapting, choosing, and building, often within imperfect systems. Her story is an example of what Indian institutions can enable when flexibility, trust, and mentorship align. As India looks to strengthen its scientific ecosystem, narratives like Sreeja’s remind us that representation is built through sustained support for diverse life paths. These everyday negotiations between science and systems, ambition and care, are what it takes to shape a more inclusive research culture.